|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

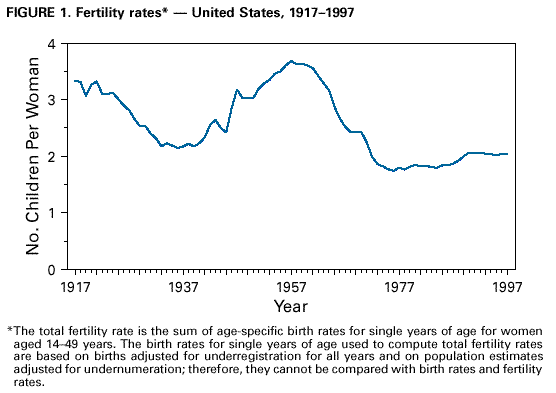

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Achievements in Public Health, 1900-1999: Family PlanningDuring the 20th century, the hallmark of family planning in the United States has been the ability to achieve desired birth spacing and family size (Figure 1). Fertility decreased as couples chose to have fewer children; concurrently, child mortality declined, people moved from farms to cities, and the age at marriage increased (1). Smaller families and longer birth intervals have contributed to the better health of infants, children, and women, and have improved the social and economic role of women (2,3). Despite high failure rates, traditional methods of fertility control contributed to the decline in family size (4). Modern contraception and reproductive health-care systems that became available later in the century further improved couples' ability to plan their families. Publicly supported family planning services prevent an estimated 1.3 million unintended pregnancies annually (5). This report reviews the history of family planning during the past century; summarizes social, legal, and technologic developments and the impact of family planning services; and discusses the need to ensure continued technologic improvements and access to care. Early History Family size declined between 1800 and 1900 from 7.0 to 3.5 children (4). In 1900, six to nine of every 1000 women died in childbirth, and one in five children died during the first 5 years of life.* Distributing information and counseling patients about contraception and contraceptive devices was illegal under federal and state laws (8,9); the timing of ovulation, the length of the fertile period, and other reproductive facts were unknown. In 1912, the modern birth-control movement began. Margaret Sanger (see box), a public health nurse concerned about the adverse health effects of frequent childbirth, miscarriages, and abortion, initiated efforts to circulate information about and provide access to contraception (9). In 1916, Sanger challenged the laws that suppressed the distribution of birth control information by opening in Brooklyn, New York, the first family planning clinic. The police closed her clinic, but the court challenges that followed established a legal precedent that allowed physicians to provide advice on contraception for health reasons. During the 1920s and 1930s, Sanger continued to promote family planning by opening more clinics and challenging legal restrictions. As a result, physicians gained the right to counsel patients and to prescribe contraceptive methods (10,11). By the 1930s, a few state health departments (e.g., North Carolina) and public hospitals had begun to provide family planning services. During the first part of the 20th century, family planning focused on the need of married couples to space children and limit family size. Among a national probability sample** of 1049 ever-married white women born during 1901-1910 and interviewed in 1978, 71% reported having practiced contraception; common techniques used were the condom (54%), contraceptive douche (47%), withdrawal (45%), rhythm (24%), and the cervical diaphragm (17%) (12). Other reported methods included infrequent sexual intercourse (8%), intermittent abstinence (6%), and contraceptive sterilization (4%).*** Using abstinence to prevent pregnancy was limited by uncertainty about the timing of a woman's ovulation. In 1928, the timing of ovulation was established medically, but the safe interval for intercourse was mistakenly understood to include half the menstrual period (13). Nevertheless, by 1933, the average family size had declined to 2.3 children. Modern Contraception Family size increased from 1940 until 1957 (Figure 1), when the average number of children per family peaked at 3.7 (14,15; CDC, unpublished data, 1999). In 1960, the era of modern contraception began when both the birth control pill and intrauterine device (IUD) became available. These effective and convenient methods resulted in widespread changes in birth control (16). By 1965, the pill had become the most popular birth control method, followed by the condom and contraceptive sterilization (16). In 1965, the Supreme Court (Griswold vs. Connecticut) (17) struck down state laws prohibiting contraceptive use by married couples. In 1970, federal funding for family planning services was established under the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act, which created Title X of the Public Health Service Act (18). Medicaid funding for family planning was authorized in 1972. Services provided under Title X grew rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s; after 1980, public funding for family planning continued to shift to the Medicaid program (18). Since 1972, the average family size has leveled off at approximately two children, and the safety, efficacy, diversity, accessibility, and use of contraceptive methods has increased (Table 2). During the 1970s and 1980s, contraceptive sterilization became more common and is now the most widely used method in the United States (16,19,20). IUD use increased during the early 1980s, then declined because of concerns about intrauterine infections (16). In the 1980s and 1990s, the use of condoms increased among adolescents, presumably because of growing concern about human immunodeficiency virus infection and other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) (21-23). Since 1991, increased use of long-acting hormonal contraception (Depo-Provera[Registered] [Pharmacia & Upjohn, Inc., Peapack, New Jersey] and Norplant[Registered] [Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories, St. Davids, Pennsylvania])**** also have contributed to the decline in adolescent pregnancy rates (24,25). Emergency use of oral contraceptive pills might reduce the risk for pregnancy after unprotected intercourse by at least 74% (26). Noncontraceptive health benefits of oral contraceptives include lower rates of pelvic inflammatory disease, cancers of the ovary and endometrium, recurrent ovarian cysts, benign breast cysts and fibroadenomas, and discomfort from menstrual cramps (27). In the United States, physicians are the primary providers of surgical sterilization, hormonal contraception, and IUDs. In 1994, 3119 agencies (e.g., health departments, Planned Parenthood affiliates, and hospitals) operated 7122 publicly subsidized family planning clinics for an estimated 6.6 million women (28). These services prevent an estimated 1.3 million unintended pregnancies annually (534,000 unintended births, 632,000 abortions, and 165,000 miscarriages) (5). Publicly supported clinics have been effective in supplying contraception to populations that have high rates of unintended pregnancy and have limited access to private health-care providers. In 1988, of the women who obtained reversible contraception, 22.5% overall received services from public clinics. Those most likely to receive these services were adolescent (43%), poor (39%), and never-married (34%) women (5). Contraception Worldwide The most important determinant of declining fertility in developing countries is contraceptive use, which explains 92% of the variation in fertility among 50 countries (29-31). Overall fertility declined by approximately one third from the 1960s through the 1980s, from an average of six to four children per woman (31), with dramatic decreases occurring in some parts of the world (e.g., 24% decline in fertility in Asia and Latin America, approximately 50% in Thailand, and approximately 35% in Colombia, Jamaica, and Mexico). As fertility declined in developing countries, the infant mortality rate decreased from approximately 150 deaths per 1000 live births in the 1950s to approximately 80 per 1000 in the early 1990s (2,3). Among married women of reproductive age in developing countries, 53% plan the size of their families (32); 90% of these women report using modern birth-control methods (e.g., female sterilization, oral contraceptives, and IUDs) (31). Challenges In the United States, unintended pregnancy remains a problem; 49% of pregnancies are unintended and 54% of these end in abortion (33). These rates remain significantly higher than rates of many other industrialized countries. During 1982-1986, among 15 Western countries with similar reproductive behavior (e.g., Canada, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom), the United States ranked fourth highest in total fertility rate and had the second highest abortion rate and the highest pregnancy rate (34). Although pregnancy and childbearing rates for adolescent women have declined since 1991, the proportion of adolescent women who are unmarried at the time of giving birth has increased (24,25) from 15% in 1960 to approximately 75% in 1998. Despite advances in family planning, population growth remains a worldwide concern. In 1999, world population reached six billion, an increase of 4.4 billion births since 1900 (35). In 1994, an international conference on population and development in Cairo focused international attention on the full scope of family planning that can be addressed during delivery of family planning services, including reproductive and primary-care concerns (36). For example, the introduction of cervical screening has led to a 20%-60% reduction in cervical cancer death rates (37). Screening programs for chlamydia, the leading cause of preventable infertility, can lower the prevalence of chlamydia and reduce complications such as pelvic inflammatory disease (38) The STD prevention benefits of family planning may be enhanced by new female-controlled barrier methods such as vaginal microbicides and the female condom. Managed care is rapidly changing patterns of health-care delivery and creating new challenges for primary and reproductive health-care providers (39). Managed-care plans often offer more comprehensive coverage of such services than traditional insurance plans (39). In the late 1990s, legislatures in 19 states mandated partial or comprehensive insurance coverage for reversible methods of contraception (40). Access to high quality contraceptive services will continue to be an important factor in promoting healthy pregnancies and preventing unintended pregnancy in this country (41). During the 20th century, restrictive policies and laws affecting family planning were largely replaced by legislative and funding support for family planning services by physicians and specialized reproductive health-care providers. Marshaling public support for efforts needed to reduce the high rate of unintended pregnancy and to provide the full array of reproductive health-care services remains a challenge. Reported by: Div of Reproductive Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC. References

* Along with family planning improvements came the public health surveillance systems needed to track population fluctuations. In 1900, the standard U.S. death certificate was created, augmenting the 1880 national death registration area (6) (Table 1); in 1915, the national birth registration area was created, combining state systems into a national system. In 1955, Growth of American Families, the first national survey of women to measure reproductive factors such as the use of contraception, infertility, and pregnancy intentions, was conducted using private funding (7). Five cycles of the federally sponsored National Survey of Family Growth (in 1973, 1976, 1982, 1988, and 1995) have continued to provide data on contraceptive methods, the use of family planning services, and other information on reproductive health of women (cycle six will include men). ** Weighted data, adjusted to the 1950 census of white, ever-married women by age, education, urban-rural residence, and number of live-born infants. *** Although 4% reported contraceptive sterilization, 28% reported having surgery before aged 50 years that rendered them infertile. **** Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Table 1 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size. TABLE 1. Milestones in family planning -- United States, 1900-1997

* Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Return to top. Figure 1  Return to top. Table 2 Note: To print large tables and graphs users may have to change their printer settings to landscape and use a small font size. TABLE 2. Efficacy of commonly used methods of contraception* and percentage of couples using the method -- United States, 1995

* For spermicides, periodic abstinence, the diaphragm, male condom, and pill, these estimates for typical use were derived from the experiences of married women in the 1976 and 1988 National Surveys of Family Growth (NSFG) and of all women in the 1988 NSFG. The estimates for the intrauterine device, sterilization, Depo-Provera®, and Norplant® were from large clinical investigations. The estimate for withdrawal was based on evidence from surveys. Perfect use is a best guess of the probabilities of method failure (pregnancy) during the first year of perfect use, i.e., when it is used consistently according to a specified set of rules. Highly rigorous scientific data are available to support estimates for implants, sterilization, pill, and the IUD. Use of trade names and commercial sources is for identification only and does not imply endorsement by CDC or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Sources: Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 12/2/1999 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||