|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

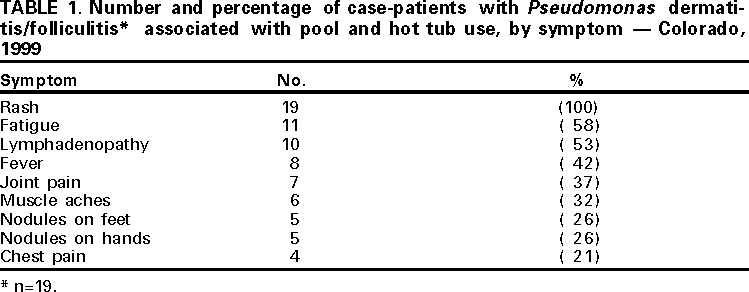

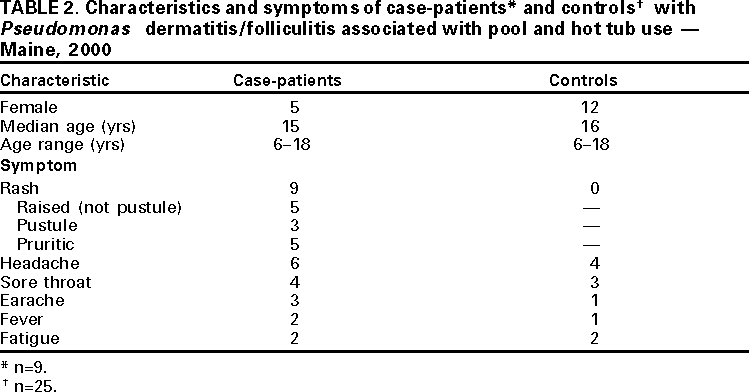

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Pseudomonas Dermatitis/Folliculitis Associated With Pools and Hot Tubs --- Colorado and Maine, 1999--2000During 1999--2000, outbreaks of Pseudomonas aeruginosa dermatitis and otitis externa associated with swimming pool and hot tub use occurred in Colorado and Maine. This report summarizes these outbreaks and provides recommendations for swimming pool and hot tub operation and maintenance, particularly when using offsite monitoring of water disinfectant and pH levels or when cyanuric acid is added to pools as a chlorine stabilizer. ColoradoIn February 1999, the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment (CDPHE) was notified of approximately 15 persons with folliculitis after they had used a hotel pool and hot tub. The cases occurred among children and adults attending two birthday parties at the hotel and among community residents who entered the pool on a pay-to-swim basis. The patients were treated for suspected Pseudomonas skin infections; one patient tested positive for Pseudomonas sp. by culture of a skin lesion. Twenty-five community residents who used the pool and/or hot tub during February 5--7, were identified through discussions with area physicians, hotel management, and other swimmers. These community residents were interviewed by CDPHE using a telephone questionnaire. Case-patients were defined as persons who developed dermatitis/folliculitis, with or without other symptoms, within 3 days of using either the pool or hot tub at the hotel during February 5--7. Questionnaires were completed for 22 (88%) of the 25 persons identified. Of the 20 persons who used the hot tub, 19 developed a rash and met the case definition. Fourteen (74%) of the 19 case-patients had more severe illness (rash >2 weeks or rash and one other symptom) (Table 1), some lasting >6 weeks. Specimens collected during the environmental inspection in May from the hot tub filter and hand rail base were positive for Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other Pseudomonas species. The pool and hot tub used separate filtration systems; each had an automated chlorination system that relied on an onsite probe to measure free chlorine and pH levels and deliver set levels of chlorine using calcium hypochlorite tablets and muriatic acid for pH control. A printout of the hourly free chlorine and pH levels in the pool and hot tub revealed that free chlorine levels dropped below state-required levels (1 mg/L) on the evening of February 4 and remained below recommended levels for approximately 69 hours. The decline in pool chlorine levels was the result of a faulty chlorine pellet dispenser. Hotel staff did not perform routine onsite water testing for the pool or hot tub. MaineThe Maine Bureau of Health (MBOH) was notified of several cases of dermatitis/folliculitis among persons who had stayed at Hotel A in Bangor, Maine, during February 18--27, 2000. To characterize the illness and determine exposures associated with illness, MBOH conducted a case--control study among persons connected with a high school basketball tournament who stayed at hotels with swimming pools and/or hot tubs in Bangor during the outbreak. Case--patients had a rash for <7 days or draining otitis externa with onset during February 18--March 3. Case--patients were matched by age and high school with healthy controls. Results from two (12.5%) schools were available for analysis. Nine persons were identified with rash, including one with otitis externa. Onset of symptoms occurred during February 20--March 1. Four of the nine persons were seen by a health-care provider. Case--patients ranged in age from 6--18 years (median age: 15 years); five were female (Table 2). The nine case--patients stayed at hotel A and spent time in either the hot tub or pool; seven spent time in both. Case--patients were more likely than controls to have spent time in the hot tub (odds ratio [OR]= 8.9; p=0.04) or to have used the pool (OR=7.4; p=0.06). The indoor pool and hot tub were located within 5 feet of each other and had separate filtration systems. Pool disinfectant and pH levels were monitored by an offsite contractor. The pool had an automated chlorination system that relied on an onsite probe to measure chlorine and pH levels and to deliver a set level of chlorine using calcium hypochlorite tablets and muriatic acid for pH control. Chlorine and pH levels were maintained manually in the hot tub. To stabilize chlorine levels, 40--60 mg/L cyanurates were used. During the outbreak, free chlorine levels were tested daily and repeatedly registered <1.0 mg/L, less than the state-required level of 1--3 mg/L, in the pool and hot tub. The pool and hot tub were crowded during the outbreak, and free chlorine levels were very low to zero after the February 25--26 weekend; no measurements were recorded over the weekend. The facilities had been cleaned thoroughly before the environmental investigation in March. Pseudomonas aeruginosa was isolated from the top of the pool filter and from the draining ear of a child aged 6 years who used the pool. Although the pulsed field gel electrophoresis patterns of the two isolates did not match, the pool isolate was obtained after the facilities had been cleaned and may not have reflected the bacterial environment of the pool during the outbreak. Reported by: G Beckett, MPH, D Williams, G Giberson, KF Gensheimer, MD, State Epidemiologist, Maine Bur of Health. K Gershman, MD, P Shillam, MSPH, RE Hoffman, MD, State Epidemiologist, Colorado Dept of Public Health and Environment; R Merry, H Savalox, L Fawcett, Eagle County Environmental Health Div, Eagle, Colorado. Hospital Infections Program, and Div of Parasitic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases; Div of Applied Public Health Training, Epidemiology Program Office; and EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a gram negative rod, is ubiquitous and can cause various mild to severe symptoms (1). Pseudomonas dermatitis and otitis externa outbreaks associated with swimming pool and hot tub use are well described (2,3); at least 75 cases during six outbreaks occurred during 1997--1998 (4). Dermatitis outbreaks usually occur as a result of low water disinfectant levels (2,3), a condition that also increases the risk for transmission of other chlorine-sensitive pathogens (e.g., Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Shigella sonnei) that may cause severe health consequences. In this report, factors that may have resulted in inadequate disinfectant levels included the use of an offsite contractor who could monitor and alert pool staff to low free chlorine or pH levels but could not change free chlorine or pH levels, and hotel employees with a minimal understanding of the offsite monitoring and alert system, pool maintenance, and the link between inadequate water disinfection and disease transmission. In addition, pools and hot tubs were not monitored routinely onsite to adjust to high bather loads that can lower free chlorine levels. In Maine, cyanuric acid was added to the indoor pool and hot tub. However, cyanuric acid, which is used to reduce chlorine loss as a result of ultraviolet light exposure, is not recommended for indoor pools or hot tubs (5,6) and is prohibited in two states (7); adding this chemical reduces the antimicrobial capacity of free chlorine (8). To reduce the risk for Pseudomonas dermatitis and the transmission of other waterborne pathogens, pool and hot tub operators should 1) adhere to pool and hot tub recommendations and regulatory requirements for pH and disinfectant levels (6,9,10); 2) have a thorough knowledge of basic aquatic facility operation; 3) provide training for pool staff on system capabilities, maintenance, and emergency alert procedures of remote monitoring systems; 4) closely monitor pool and hot tub free chlorine measurements during periods of heavy bather loading; 5) monitor hot tub disinfectant levels closely because the higher temperatures maintained serve to dissipate chlorine rapidly; and 6) understand appropriate use and effects of cyanurates on disinfection and testing. In addition, remote-monitoring companies should be timely in notifying swimming-facility staff about low disinfectant levels. Swimmers should be educated about the potential for waterborne disease transmission in pools and hot tubs, which could increase advocacy for improved maintenance and monitoring by pool operators. References

Table 1  Return to top. Table 2  Return to top. Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 12/7/2000 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 5/2/01

|