|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

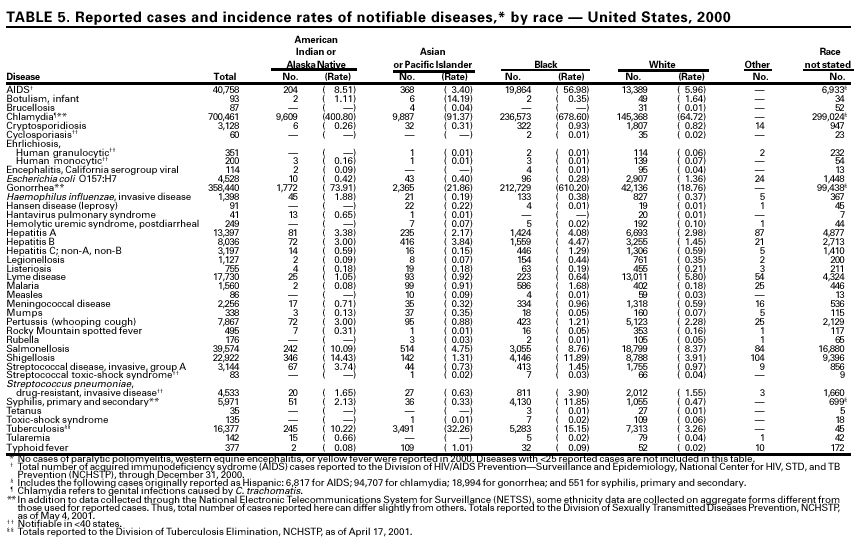

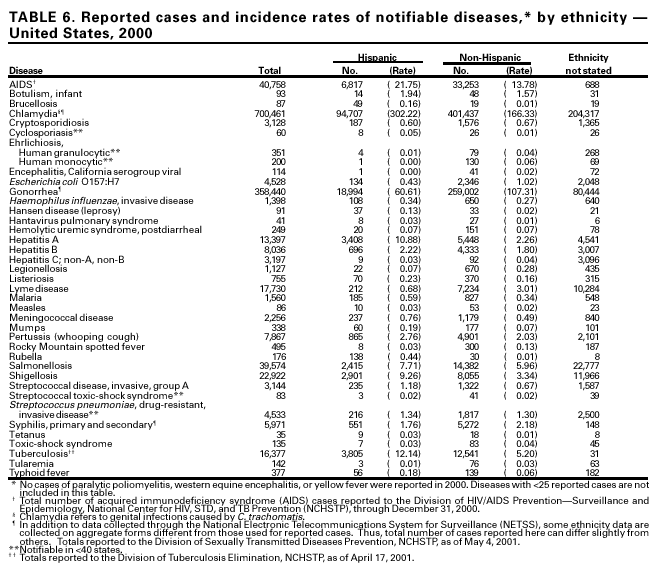

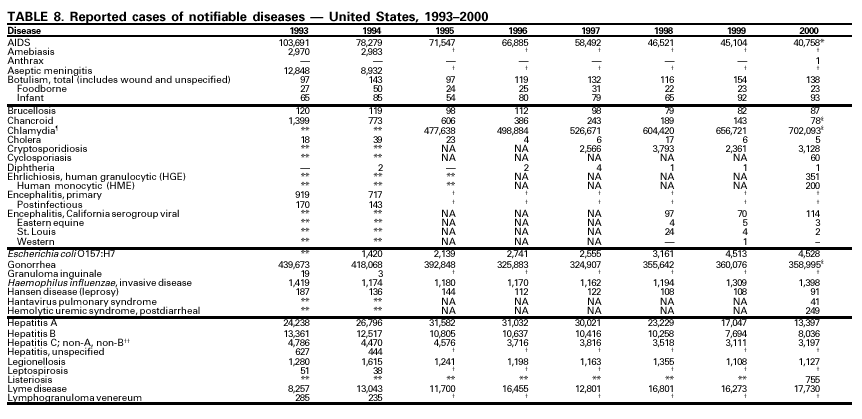

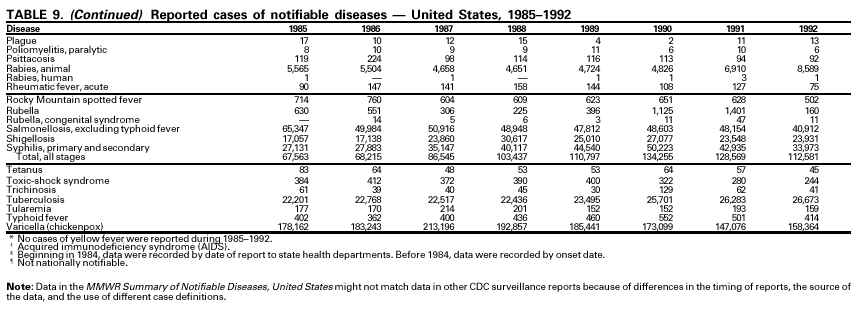

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Summary of Notifiable Diseases --- United States, 2000The following CDC staff members contributed to this report: Samuel L. Groseclose, D.V.M., M.P.H. in collaboration with Scott Noldy PrefaceThe MMWR Summary of Notifiable Diseases, United States, 2000 contains, in tabular and graphical form, the official statistics for the reported occurrence of nationally notifiable diseases in the United States for 2000. These statistics are collected and compiled from reports to the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (NNDSS), which is operated by CDC in collaboration with the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE). The Summary is located on the Internet at <http://www2.cdc.gov/mmwr/summary.html>. This site also includes publications from past years. Because dates of onset or diagnosis for notifiable diseases are not always reported, surveillance data are presented by the week they were reported to CDC by public health officials in state and territorial health departments. Data are finalized and published each year in the Summary for use by state and local health departments; schools of medicine and public health; communications media; local, state, and federal agencies; and other agencies or persons interested in following the trends of reportable diseases in the United States. This publication also documents which diseases are considered national priorities for notification and the annual number of cases of such diseases. The Highlights section presents information on selected nationally notifiable diseases to provide a context in which to interpret surveillance and disease-trend data and to provide further information on the epidemiology and prevention of selected diseases. Past publications included information on selected non-notifiable diseases, but in 1999, the Summary began presenting only highlights of nationally notifiable diseases. Part 1 contains tables of incidence data for each disease considered nationally notifiable during 2000.* These tables provide the number of cases of notifiable diseases reported to CDC for 2000, as well as the distribution of cases by month and geographic location and by patient's age, sex, race, and Hispanic ethnicity. Data are final totals as of August 24, 2001, unless otherwise noted. In all tables, leprosy is listed as Hansen disease, and tickborne typhus fever is listed as Rocky Mountain spotted fever (RMSF). In addition, syphilis (all stages) includes the following categories: latent; early latent; late latent; latent of unknown duration; neurosyphilis; late, with clinical manifestations other than neurosyphilis; syphilitic stillbirth; and congenital syphilis. Part 2 contains graphs and maps that depict summary data for many of the notifiable diseases described in tabular form in Part 1. Part 3 contains tables of the number of cases of notifiable diseases reported to CDC since 1969. This section also includes a table enumerating deaths associated with specified notifiable diseases reported to the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS), CDC, during 1989--1998. The Selected Reading section presents general and disease-specific references for notifiable infectious diseases. These references provide additional information on surveillance and epidemiologic issues, diagnostic issues, and disease-control activities. ____________________ BackgroundAs of January 1, 2000, a total of 60 infectious diseases were designated as notifiable at the national level. A notifiable disease is one for which regular, frequent, and timely information regarding individual cases is considered necessary for the prevention and control of the disease. This section briefly summarizes the history of the reporting of nationally notifiable diseases in the United States. In 1878, Congress authorized the U.S. Marine Hospital Service (the forerunner of the Public Health Service [PHS]) to collect morbidity reports regarding cholera, smallpox, plague, and yellow fever from U.S. consuls overseas. The intention was to use this information to institute quarantine measures to prevent the introduction and spread of these diseases into the United States. In 1879, a specific Congressional appropriation was made for the collection and publication of reports of these notifiable diseases. Congress expanded the authority for weekly reporting and publication of these reports in 1893 to include data from states and municipal authorities. To increase the uniformity of the data, Congress enacted a law in 1902 directing the Surgeon General to provide forms for the collection and compilation of data and for the publication of reports at the national level. In 1912, state and territorial health authorities in conjunction with PHS recommended immediate telegraphic reporting of five infectious diseases and the monthly reporting, by letter, of 10 additional diseases. The first annual summary of The Notifiable Diseases in 1912 included reports of 10 diseases from 19 states, the District of Columbia, and Hawaii. By 1928, all states, the District of Columbia, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico were participating in national reporting of 29 specified diseases. At their annual meeting in 1950, state and territorial health officers authorized the Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists (CSTE) to determine which diseases should be reported to PHS. In 1961, CDC assumed responsibility for the collection and publication of data concerning nationally notifiable diseases. The list of nationally notifiable diseases is revised periodically. For example, a disease might be added to the list as a new pathogen emerges, or a disease might be deleted as its incidence declines. Public health officials at state health departments and CDC continue to collaborate in determining which diseases should be nationally notifiable. CSTE, with input from CDC, makes recommendations annually for additions and deletions. Although disease reporting is mandated by legislation or regulation at the state and local levels, state reporting to CDC is voluntary. Thus, the list of diseases considered notifiable varies slightly by state. All states generally report the internationally quarantinable diseases (i.e., cholera, plague, and yellow fever) in compliance with the World Health Organization's International Health Regulations. Infectious Diseases Designated as Notifiable at the National Level During 2000 Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) ____________________ Data SourcesProvisional data concerning reported occurrence of notifiable diseases are published weekly in MMWR. After each reporting year, staff members in state health departments finalize reports of cases for that year with local or county health departments and reconcile the data with reports previously sent to CDC throughout the year. These data are compiled in final form in the Summary. Notifiable disease reports are the authoritative and archival counts of cases. They must be approved by the appropriate epidemiologist from each submitting state or territory before being published in the Summary. Although useful for detailed epidemiologic analyses, data published in CDC Surveillance Summaries or other surveillance reports produced by CDC programs might not agree with data reported in the Summary because of differences in the timing of reports, source of data, and case definitions. Data in the Summary were derived primarily from reports transmitted to the Division of Public Health Surveillance and Informatics, Epidemiology Program Office, CDC, from health departments in the 50 states, five territories, New York City, and the District of Columbia through the National Electronic Telecommunications System for Surveillance (NETSS). More information regarding NETSS and notifiable diseases, including case definitions for these conditions, is available on the Internet at <http://www.cdc.gov/epo/phs.htm>. Policies for reporting notifiable disease cases can vary by disease or reporting jurisdiction, depending on case status classification (i.e., confirmed, probable, or suspect). Final data for selected diseases (presented in Parts 1, 2, and 3 of the Summary) are from the surveillance records of CDC programs listed below. Requests for further information regarding these data should be directed to the appropriate program.

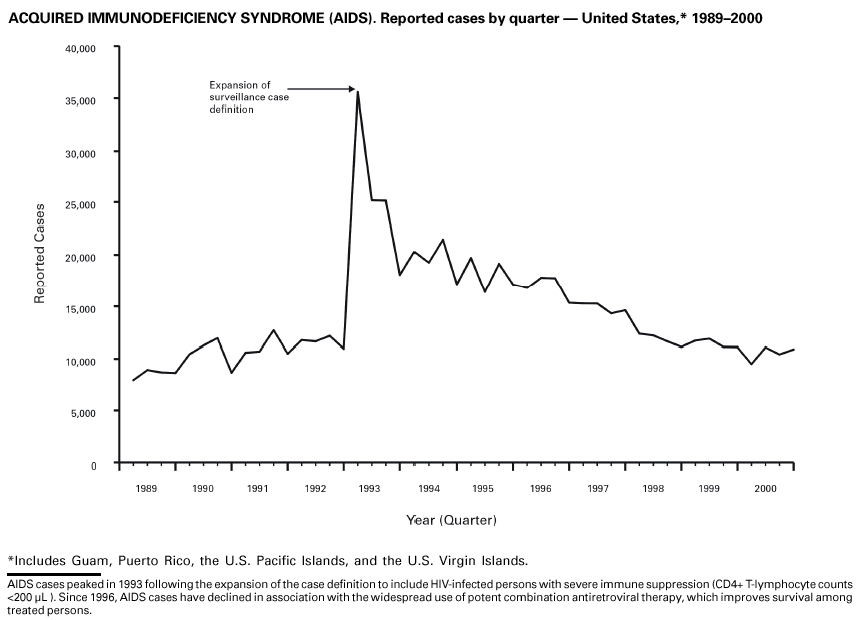

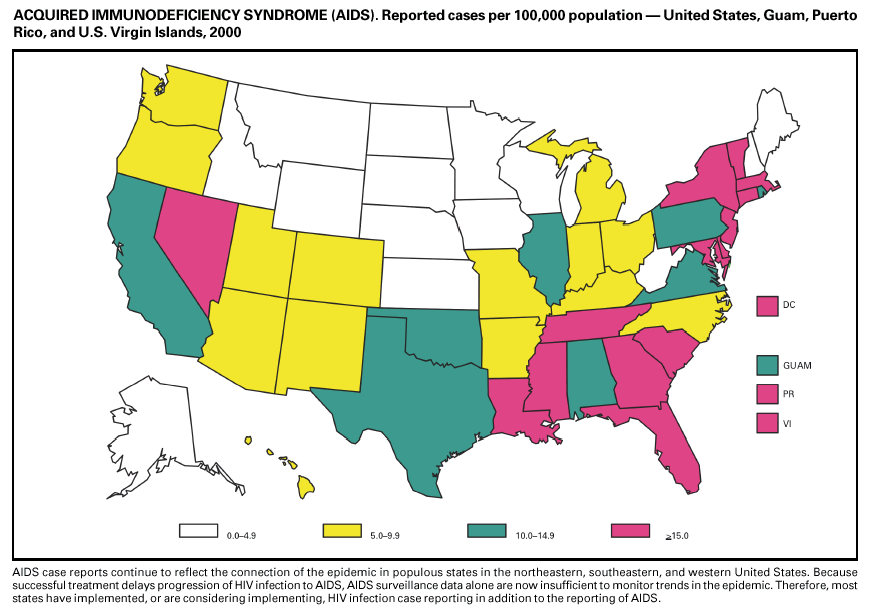

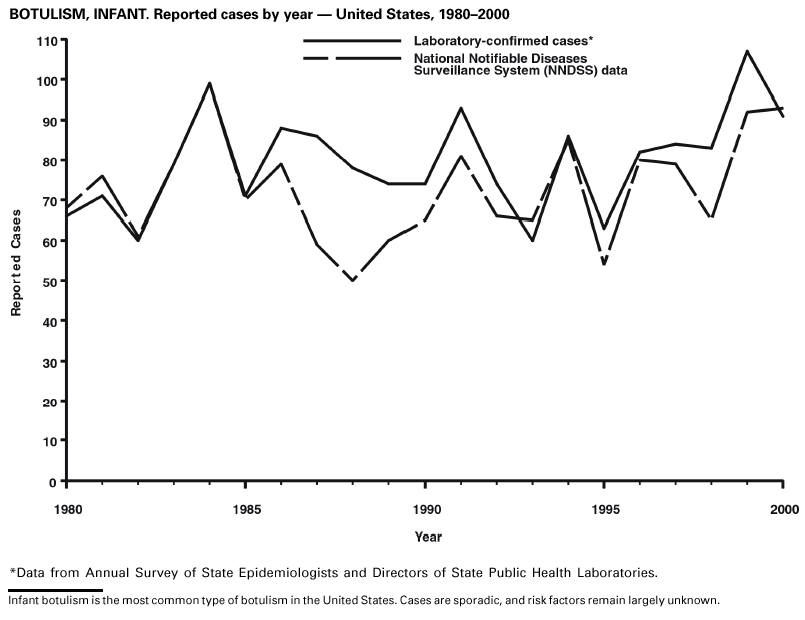

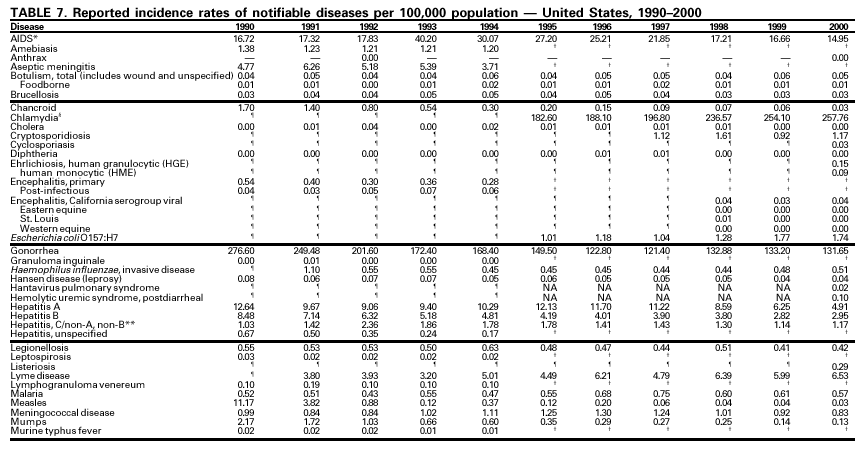

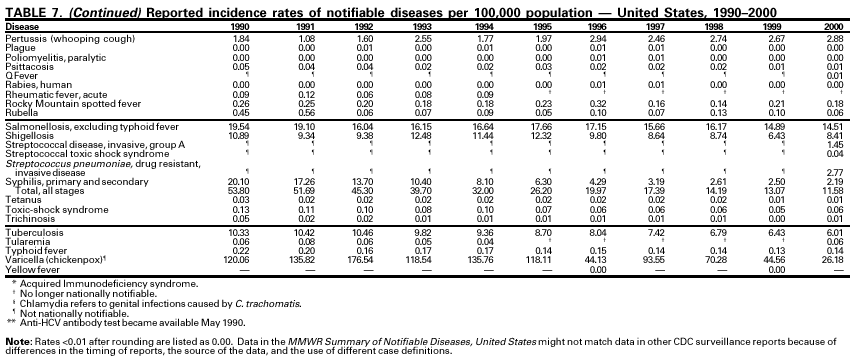

Disease totals for the United States, unless otherwise stated, do not include data for American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, the U.S. Virgin Islands, or the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI). Population estimates for the states are from the Bureau of the Census (19911999, machine readable files). Population numbers for territories are 1998 estimates from the Bureau of the Census press releases PR-99-1* and CB98-219.† More information regarding census estimates is available at <http://www.census.gov/>. Rates in the Summary are presented as incidence rates per 100,000 population based on data for the U.S. total-resident population. Population data from states in which diseases were not notifiable or disease data were not available were excluded from rate calculations. The denominator used for infant botulism rate calculation is restricted to persons aged <1 year. Interpreting Data Data reported in the Summary are useful for analyzing disease trends and determining relative disease burdens. However, data must be interpreted in light of reporting practices. Certain diseases that cause severe clinical illness (e.g., plague and rabies) are most likely reported accurately if they are diagnosed by a clinician. However, persons who have diseases that are clinically mild and infrequently associated with serious consequences (e.g., salmonellosis) might not seek medical care from a health-care provider. Even if these less severe diseases are diagnosed, they are less likely to be reported. The degree of completeness of data reporting also is influenced by the diagnostic facilities available; control measures in effect; public awareness of a specific disease; and interests, resources, and priorities of state and local officials responsible for disease control and public health surveillance. Finally, factors such as changes in case definitions for public health surveillance, introduction of new diagnostic tests, or discovery of new disease entities can cause changes in disease reporting that are independent of the true incidence of disease. Public health surveillance data are published for selected racial and ethnic population groups because these variables can be risk markers for certain notifiable diseases. Risk markers can identify potential risk factors for investigation in future studies. Race and ethnicity data also can be used to target populations for prevention efforts. However, caution must be used when drawing conclusions from reported race and ethnicity data. Certain racial/ethnic population groups have differential patterns of access to health care, potentially resulting in data that are not representative of disease incidence in these populations. In addition, not all race and ethnicity data are collected uniformly for all diseases. For example, in NCHSTP, the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention Surveillance and Epidemiology and the Division of Sexually Transmitted Diseases Prevention collect race/ethnicity data using a single variable. A person's race/ethnicity is reported as American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian/Pacific Islander, black non-Hispanic, white non-Hispanic, or Hispanic. Additionally, although the recommended standard for classifying a person's race or ethnicity is based on self-reporting, this procedure might not always be followed. ____________________ † Available at <http://www.census.gov/Press-Release/www/1999/cb99-254.html>. Highlights for 2000This section presents information on the public health importance of selected nationally notifiable diseases reported from the states to CDC, including a) domestic and some international disease outbreaks, b) active surveillance findings, c) changes in data reporting practices, d) the impact of prevention programs, e) the emergence of antimicrobial resistance, and f) changes in immunization policies. This information is intended to provide a context in which to interpret surveillance and disease-trend data and to provide further information on the epidemiology and prevention of selected diseases. AIDS* As of December 31, 2000, a total of 774,467 acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) cases were reported; 448,060 cases resulted in death, and 3,542 cases had unknown vital status. Of the total, approximately one third of cases were reported during 1993--1995 and 1996--2000; the remaining third were reported before 1993. The number of persons presumed living with AIDS (322,865) at the end of 2000 was the highest ever reported; of these persons, 79% were men, 61% were black or Hispanic, and 41% were infected through male-to-male sex. Since 1981, approximately 85% of persons diagnosed with AIDS have been aged 20--49 years (1). From January 1998 through June 2000, AIDS incidence and deaths leveled off, but AIDS prevalence continued to increase. The number of reported cases is affected by epidemic trends and other factors that can affect case reporting (e.g., changes in the AIDS surveillance case definition and widespread introduction of effective treatments). To provide better data for prevention of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection (the virus that causes AIDS), CDC and CSTE recommend that national surveillance include the monitoring of both HIV infection and AIDS (2,3). CDC supports several supplemental surveillance projects that collect data on barriers to preventing AIDS cases and death of persons with AIDS, including access to HIV testing and treatment in accordance with current public health service guidelines.

____________________ Chancroid During 2000, a total of 78 cases of chancroid were reported (rate: 0.03 cases/100,000 population), representing a 45% decline from 1999 and a continuing decline since 1987 (1). However, chancroid is difficult to culture and could be substantially underdiagnosed. Several studies that used DNA amplification tests (which are not commercially available) have identified this infection in cities where it was previously undetected (2).

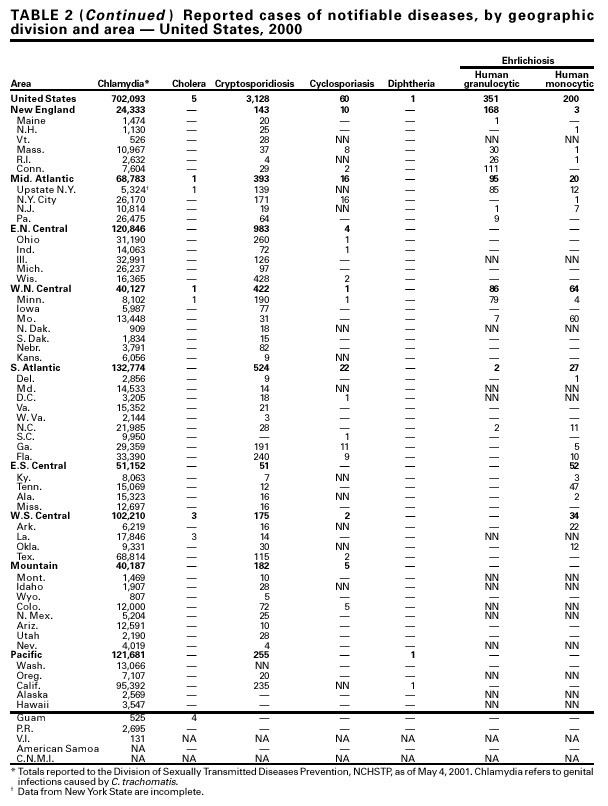

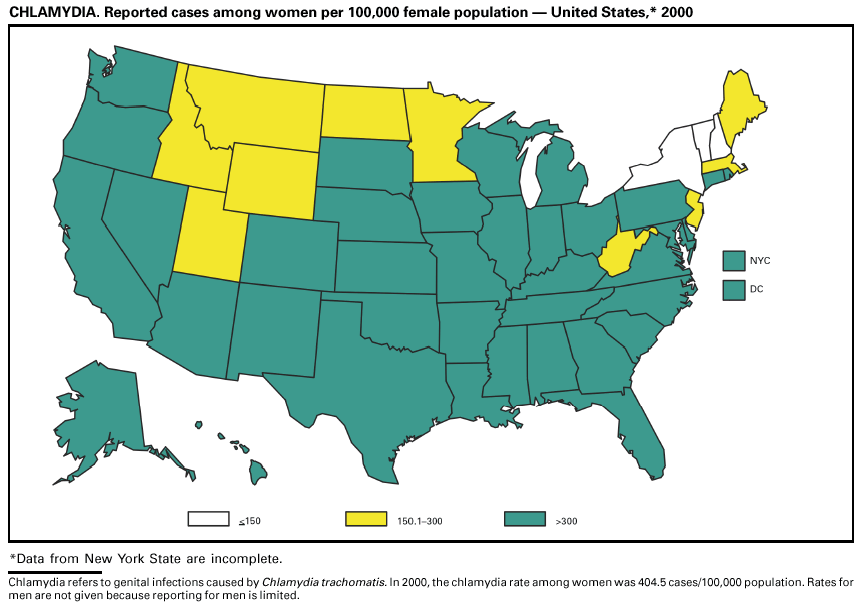

Chlamydia trachomatis, Genital Infection During 2000, a total of 702,093 cases of genital chlamydial infection were reported (rate: 257.5/100,000). This rate was the highest since voluntary case reporting began in the mid-1980s and the highest since genital chlamydial infection became a nationally notifiable disease in 1995 (1). This increase could be caused in part by the continued expansion of chlamydia screening programs and increased use of more sensitive diagnostic tests for this condition. Since the late 1980s, data on chlamydia prevalence obtained by monitoring test positivity rates of persons screened in different clinic settings have generally documented declining levels of infection in many parts of the United States (1).

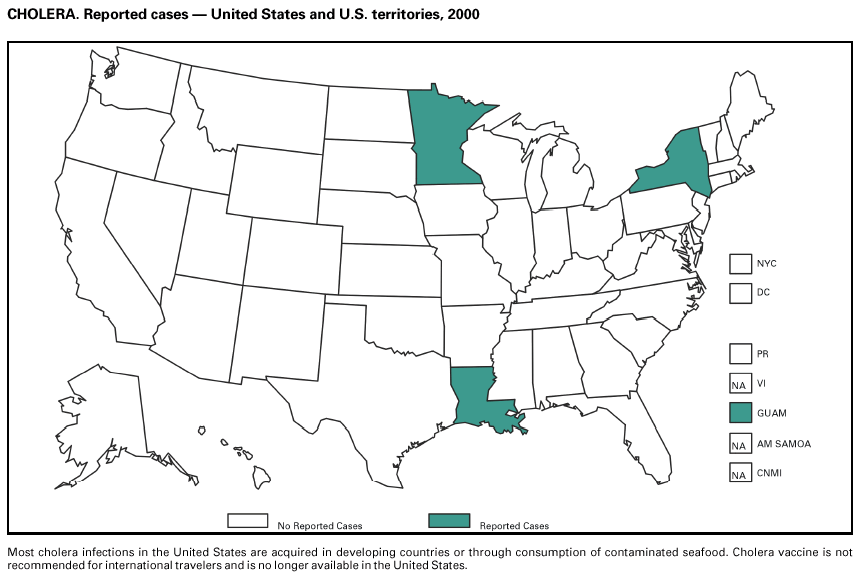

Cholera During 1995--2000, a total of 61 laboratory-confirmed cases of cholera, all caused by Vibrio cholerae O1, were reported. Thirty-five (57%) patients were hospitalized, and one died. Thirty-seven (61%) infections were acquired outside the United States, whereas six (10%) were acquired through consumption of contaminated seafood harvested in Gulf Coast waters. Among the 37 travel-associated cholera cases, 31% of isolates were resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, sulfisoxazole, streptomycin, and furazolidone. Thus, foreign travel and contaminated seafood continue to account for most cholera cases in the United States, and antimicrobial resistance is increasing among V. cholerae O1 strains isolated from ill travelers (1). Production and sale of the only licensed cholera vaccine in the United States ceased in 2001.

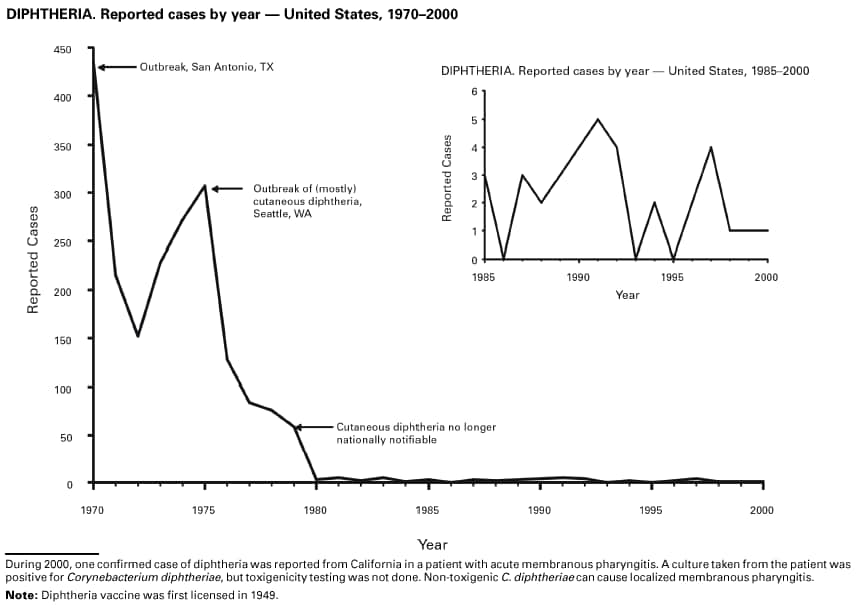

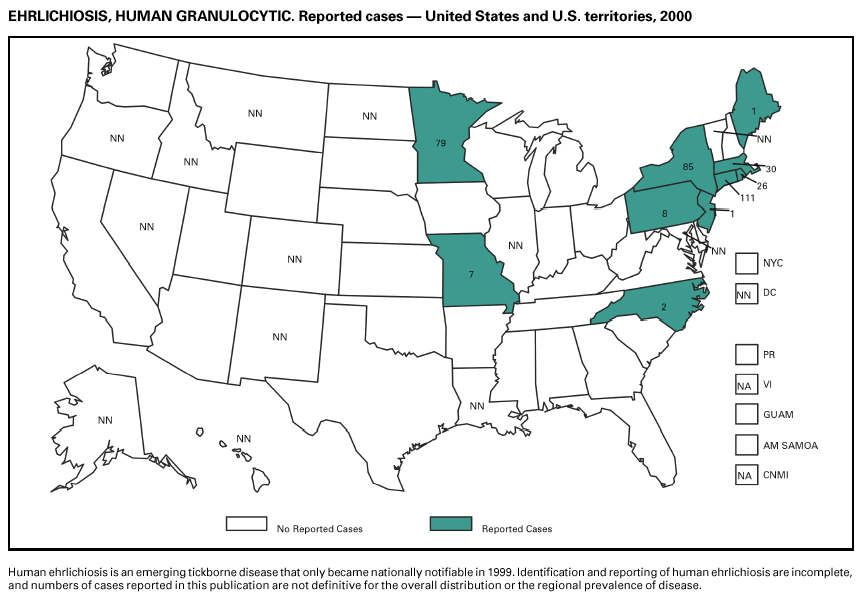

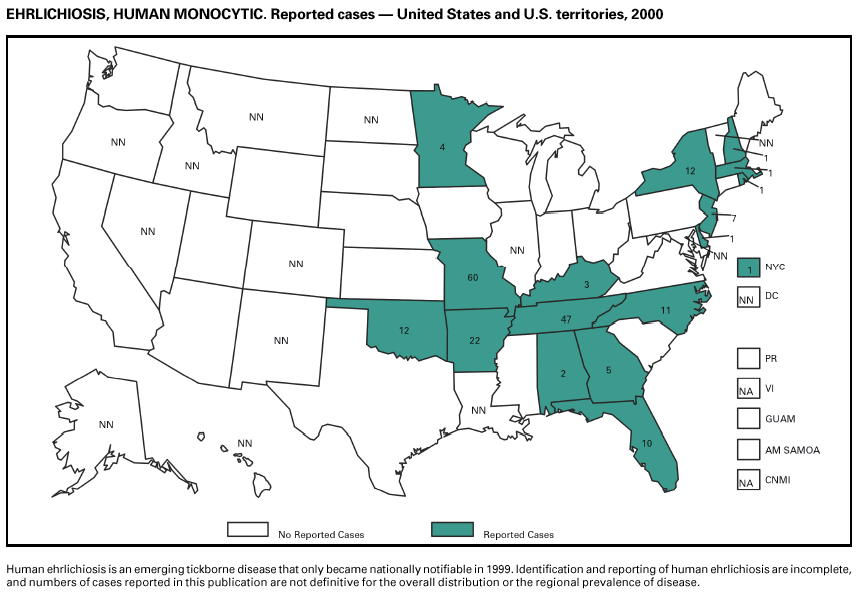

Diphtheria During 2000, one confirmed case of diphtheria was reported from California in a female patient aged 86 years who had acute membranous pharyngitis. A culture taken from the patient was positive for Corynebacterium diphtheriae, but toxigenicity testing was not conducted. Non-toxigenic C. diphtheriae can cause localized membranous pharyngitis. Ehrlichiosis During 2000, the second full year of national reporting of the emerging tick-borne zoonosis ehrlichiosis, 200 cases of human monocytic ehrlichiosis (HME) and 351 cases of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE) were reported through NETSS. By comparison, 99 cases of HME and 203 cases of HGE were reported during 1999 (1) Through December 2000, ehrlichiosis was a notifiable disease in 36 states, compared with 19 states through August 1998 (2). In 2000, CSTE changed the case definition for human ehrlichiosis. A third reporting category (i.e., ehrlichiosis, other or unspecified agent) was added to clarify reporting criteria and provide a mechanism for classifying and reporting cases caused by unspecified or novel Ehrlichia species, including E. ewingii (3). In addition to reporting via NETSS, case information on the three categories of ehrlichiosis also should be reported on the revised Tick-Borne Rickettsial Disease Case Report form (CDC 55.1 Rev. 01/2001), which was distributed to state health departments in April 2001 and replaces all previous Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever Case Report forms. Copies of this form are available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/ehrlichia> and <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/rmsf>.

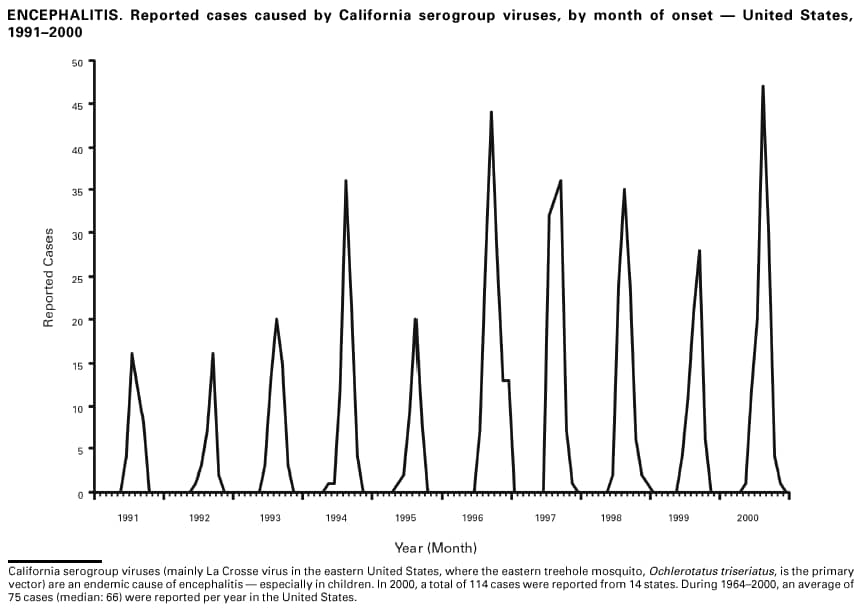

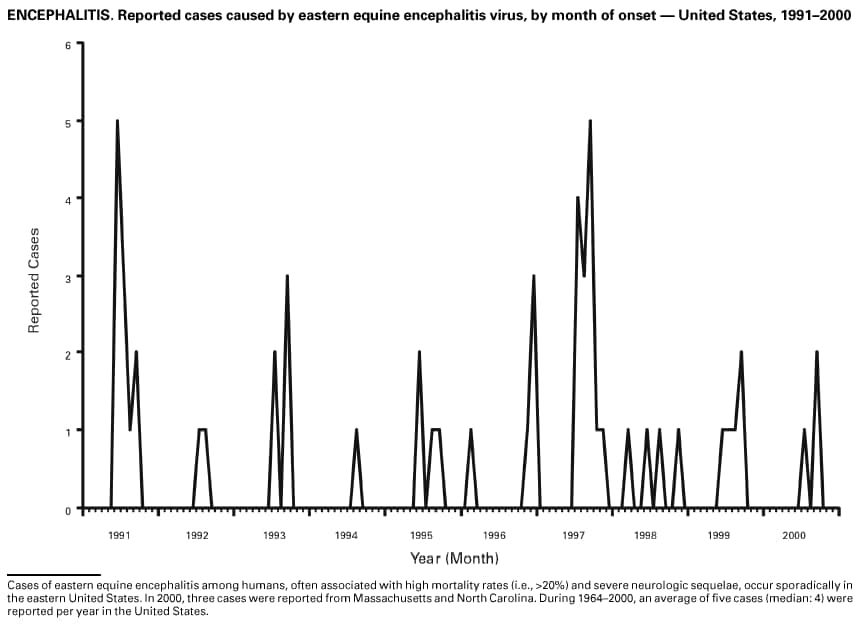

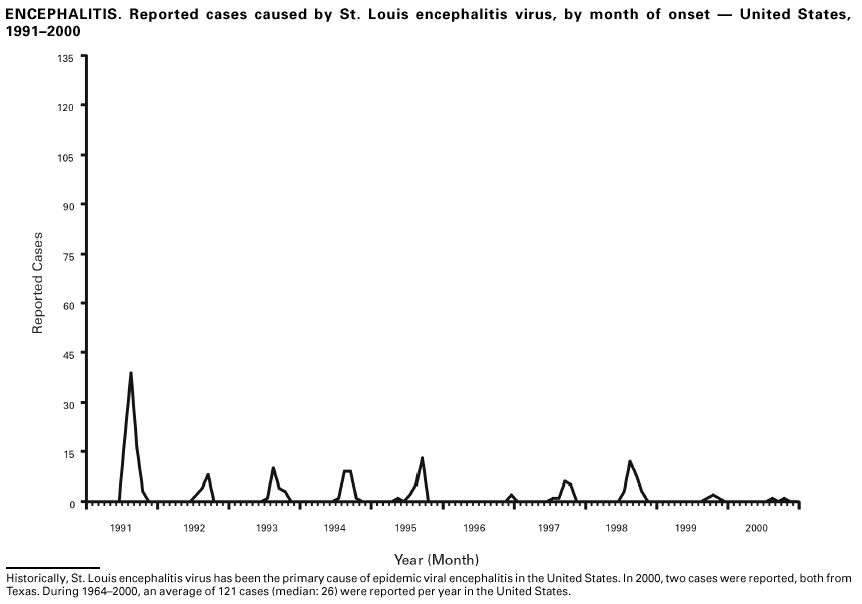

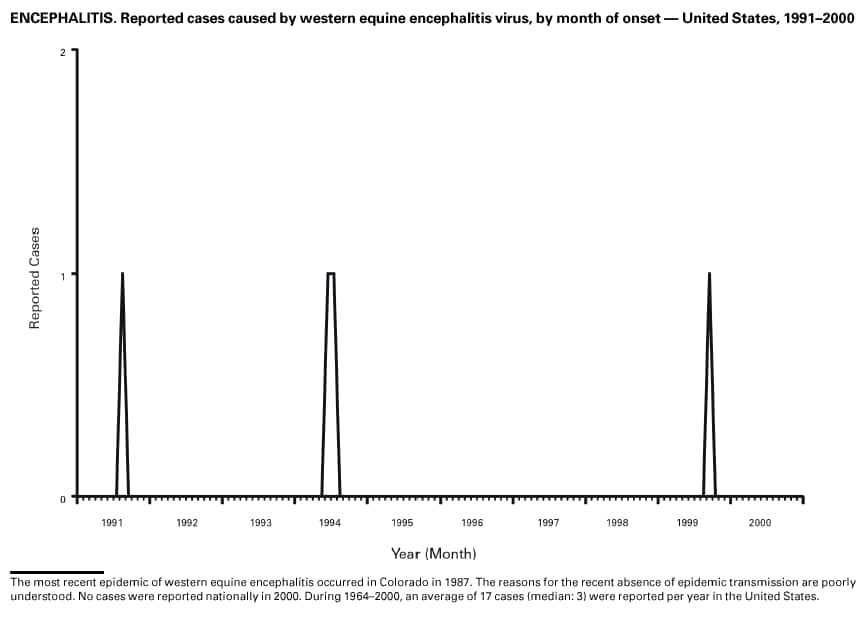

Encephalitis During 1999, a summer epidemic of acute meningoencephalitis of unknown etiology in the greater New York City area, with 62 human cases and seven fatalities, signaled the first known introduction of West Nile virus from the Eastern Hemisphere to the Western Hemisphere (1). Urban Culex species were the apparent primary mosquito vectors to humans. Birds were the primary amplifying hosts, and unprecedented morbidity and mortality were observed among some native bird species, especially crows. Previously, the known geographic distribution of West Nile virus included Africa, West Asia, and Europe (2). West Nile virus is related closely to St. Louis encephalitis virus, historically the major cause of epidemic viral encephalitis in the United States. During early 2000, West Nile virus was detected in dormant mosquitoes collected in the northeastern United States, indicating its successful overwintering and potential reemergence across a larger area of the eastern United States during the following spring and summer (3). During the summer and fall of 2000, a total of 21 cases of West Nile viral disease among humans were reported from the greater New York City area (14 in New York, six in New Jersey, and one in Connecticut); two of these cases were fatal (4).

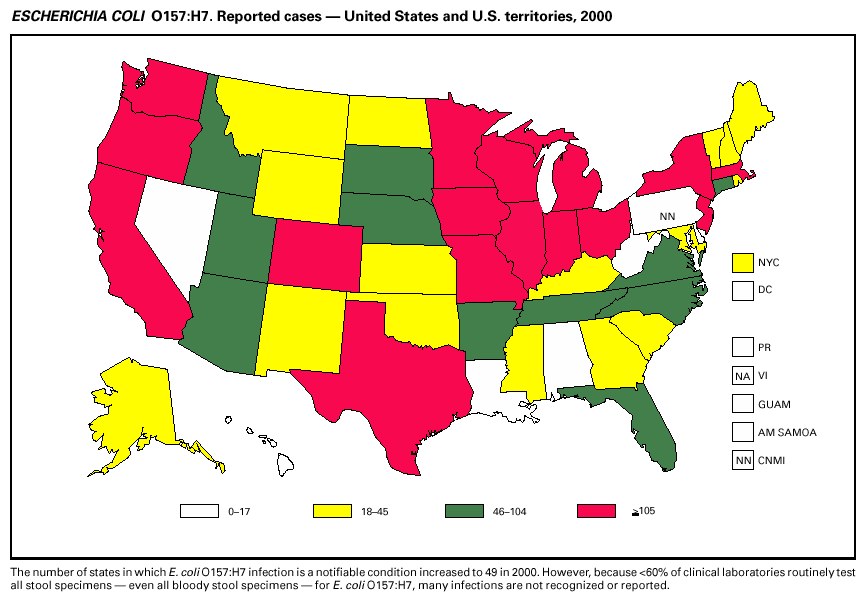

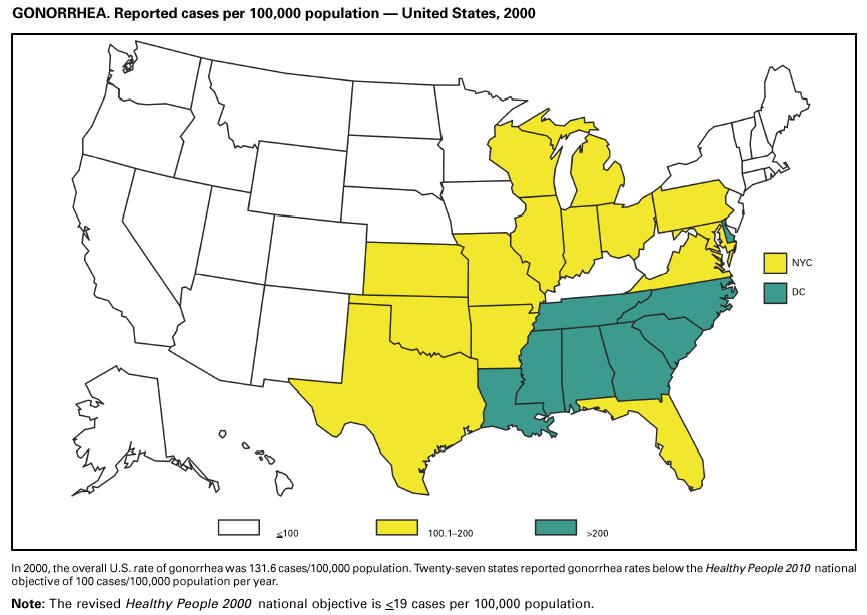

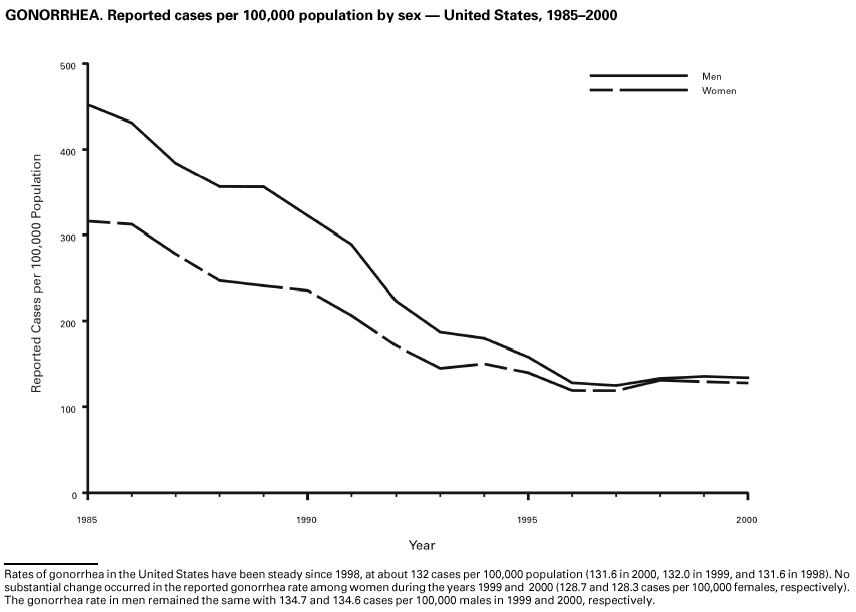

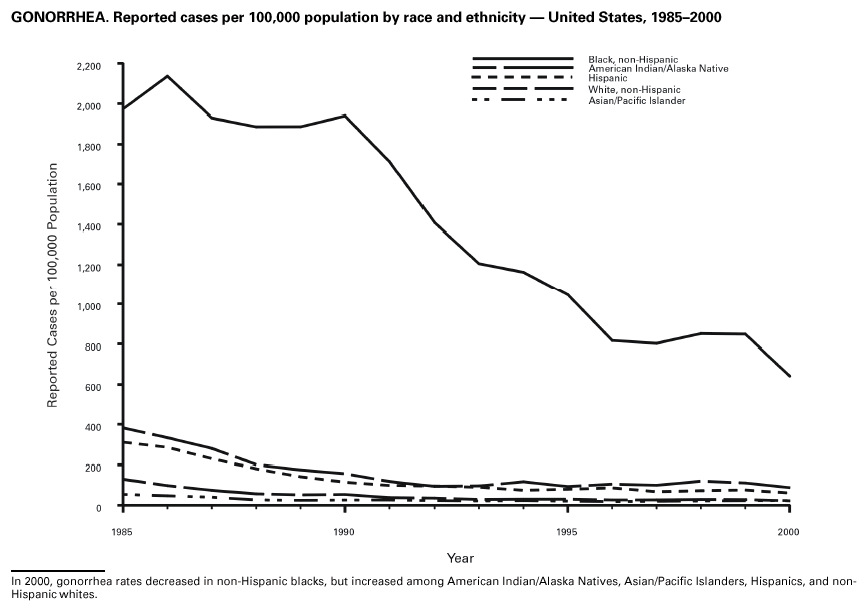

Gonorrhea During 2000, a total of 358,995 cases of gonorrhea were reported (rate: 131.6/100,000). The 2000 rate was similar to rates for 1999 (132.0/100,000) and 1998 (121.4/100,000) (1). Although rates have stabilized, increases have been observed in some areas among men who have sex with men (2). Additionally, decreased susceptibility to the fluoroquinolone antibiotics and azithromycin has been reported from some regions (3).

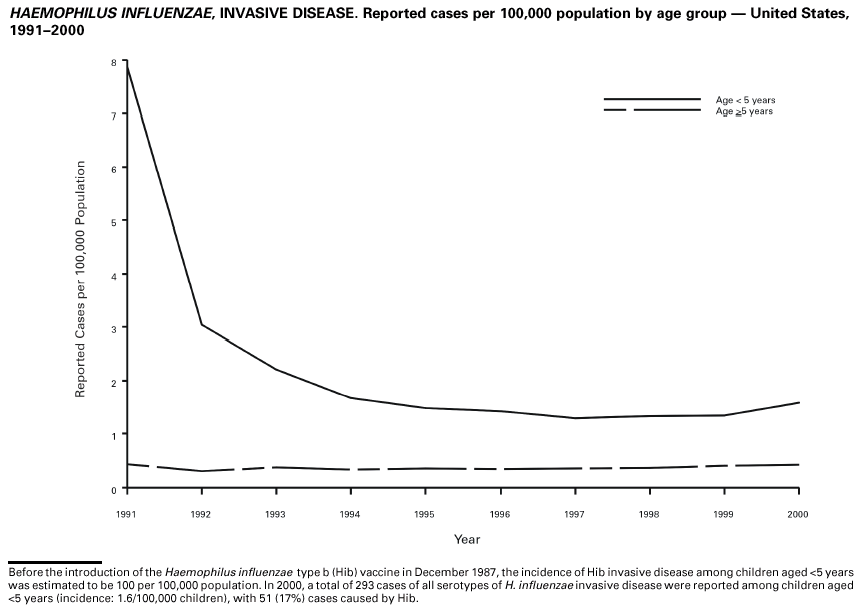

Haemophilus influenzae, Invasive Disease During 2000, a total of 293 cases of Haemophilus influenzae (Hi) invasive disease among children aged <5 years were reported.* Before a vaccine was introduced in 1987, approximately 20,000 cases of H. influenzae type b (Hib) invasive disease occurred among children annually (1). Because of widespread use of the Hib vaccine among preschool-aged children, the number of Hib cases has declined sharply. Of the 293 cases reported during 2000, a total of 227 (78%) Hi isolates were serotyped, and 55 (24%) of these were type b. Among the 55 cases of Hib invasive disease reported among children aged <5 years, 23 (42%) were among those aged <6 months, who had not completed a two- or three-dose primary Hib vaccination. However, 23 (72%) of the 32 children who were old enough (i.e., aged >6 months) to have completed a three-dose primary series either had unknown vaccination status (six children) or were incompletely or not vaccinated (17 children). Data as of August 2001 are provided to the National Immunization Program Office.

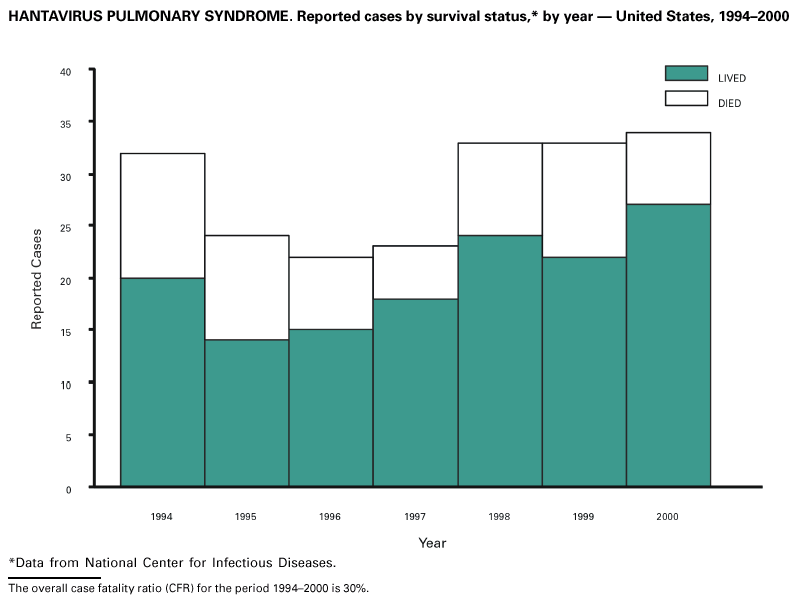

Hantavirus Pulmonary Syndrome During 2000, a total of 41 probable cases of hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (HPS) were reported from 10 states. Of the 34 cases laboratory confirmed by CDC, seven (21%) were fatal. Since 1993, a total of 256 cases from 30 states have been confirmed. An additional 32 cases were identified retrospectively back to 1959. Cases of HPS have now been recognized in countries throughout the Western Hemisphere. Reports of confirmed cases in patients with mild disease that does not meet the clinical criteria for HPS are increasing (1). Treatment is available only for the symptoms of HPS, as a 19931994 open-label trial of the antiviral drug ribavirin did not suggest a benefit (2). Although most HPS in the United States is caused by Sin Nombre virus and its variants (i.e., New York and Monongahela), some cases have been associated with other hantaviruses, including Bayou and Black Creek Canal. Virus is shed in rodent urine, feces, and saliva and is primarily transmitted through inhalation. Since the initial recognition of HPS in 1993, researchers continue to investigate the probable relationship between environmental conditions and reports of HPS cases (3,4).

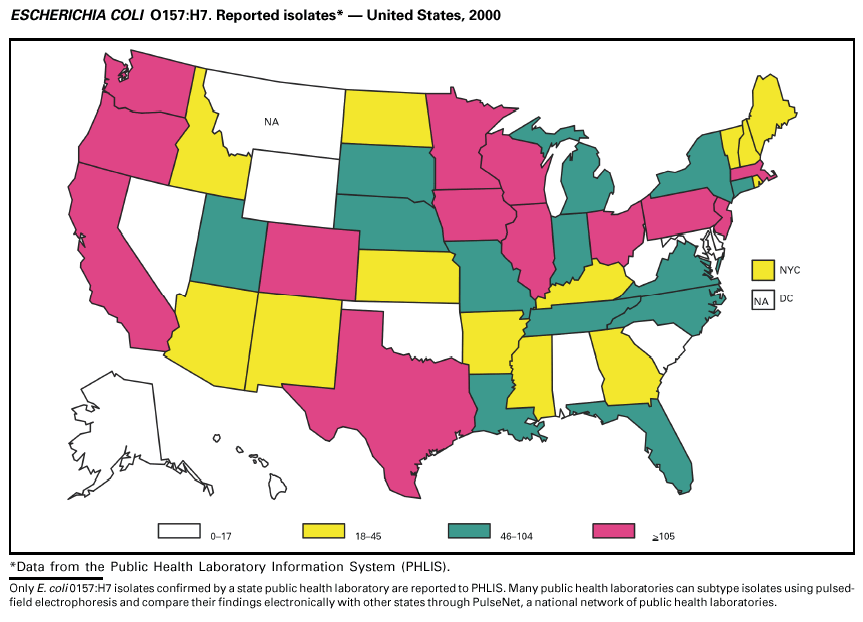

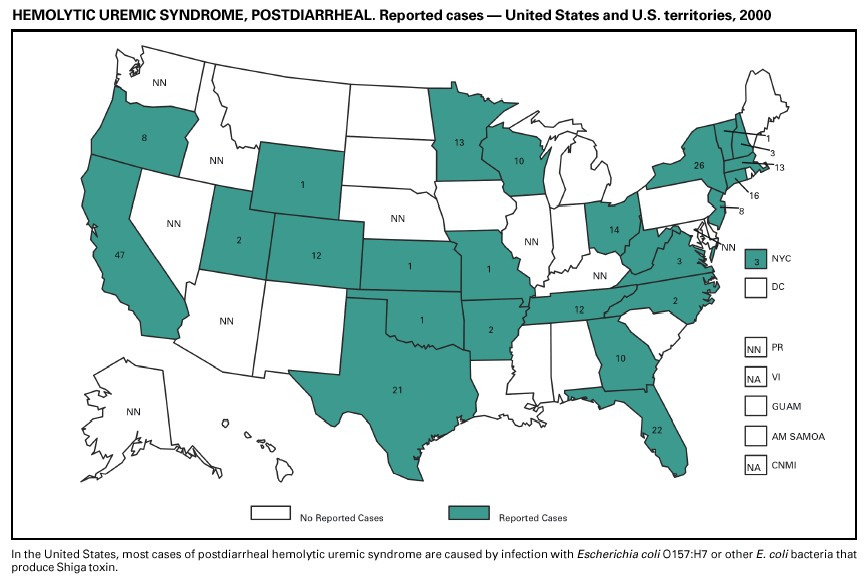

____________________ Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, Postdiarrheal During 2000, the fifth year of national reporting, 24 states reported 249 cases of postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS). The median age of patients was 4 years (range: <191), and 56% were female. Illness was seasonal, with 45% of cases occurring from June through September. By comparison, 26 states reported 181 cases in 1999, and 17 states reported 119 cases in 1998. Though the number of areas reporting and the number of cases reported increased in 2000, the increased number of cases is likely a result of improved ascertainment rather than a change in incidence. Eight states and at least one territory did not list HUS as a notifiable disease in 2000, contributing to substantial underreporting. Postdiarrheal HUS is a life-threatening illness characterized by hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and renal injury. In the United States, most cases are caused by infection with Escherichia coli O157:H7; some are caused by other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (1,2).

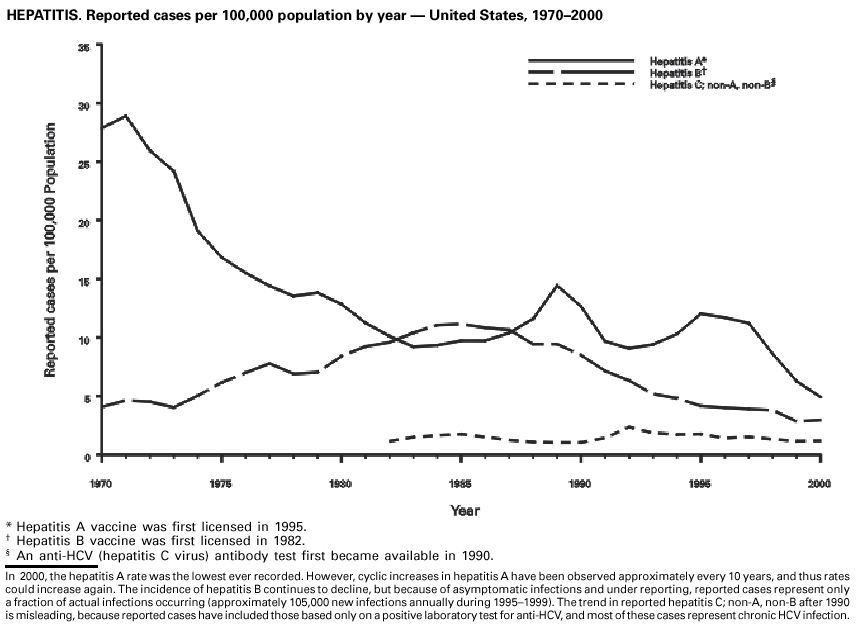

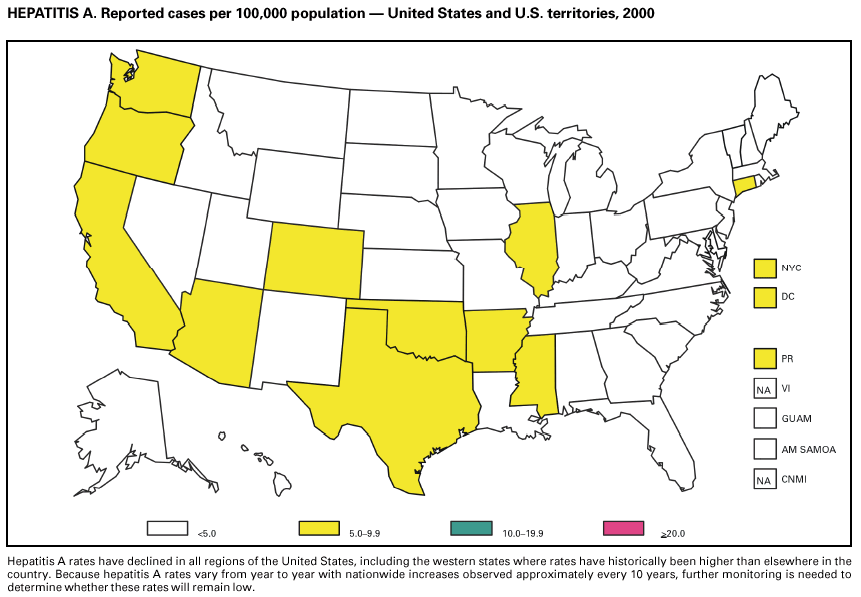

Hepatitis A During 2000, the overall hepatitis A rate (4.9/100,000) reported was the lowest ever recorded. However, because hepatitis A rates tend to vary from year to year and from region to region, determining whether this low rate was caused by routine immunization or natural variability in infection rates is not possible. Monitoring hepatitis A incidence to determine if these low rates are sustained over time is critical to assessing the impact of routine vaccination. Routine childhood hepatitis A vaccination is recommended in the 11 states where the average annual hepatitis A rate during 1987--1997 was >20 cases/100,000 (i.e., approximately twice the national average) (1). Routine childhood vaccination should be considered in the six states where the average rate during 1987--1997 was approximately 10--20/100,000. Hepatitis B During 2000, a total of 8,036 acute hepatitis B cases were reported, representing a >60% decrease since 1990 (21,102 cases). Surveillance data are being used to monitor the impact of the national strategy for eliminating hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection. Healthy People 2010 objectives call for a 75%--90% reduction in the national incidence of hepatitis B among adults (baseline: 15--24 cases/100,000), a 99% reduction among children aged 2--18 years (baseline: 945 cases/year), and a 75% reduction in the number of perinatal HBV infections (baseline: 1,682 infections/year) (1). Reported hepatitis B cases can be used to monitor the occurrence of disease among adults. However, because most infections among infants and young children are asymptomatic, reported cases underestimate the incidence of disease in these age groups. Thus, data from other sources (e.g., serosurveys) are needed to monitor progress toward eliminating HBV transmission among younger age groups.

Hepatitis C; Non-A, Non-B Cases of hepatitis C reported to CDC are considered unreliable because a) no serologic marker for acute infection exists and b) most health departments do not have the resources to determine if a positive laboratory report for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection represents acute infection, chronic infection, repeated testing of a person previously reported, or a false-positive result (1). Historically, the most reliable national estimates of acute disease incidence have come from sentinel surveillance. After adjusting for underreporting and asymptomatic infections, the annual number of new infections has decreased >80% since 1989 to 35,000 cases in 1999 (CDC, unpublished data, 2000). Because surveillance for acute hepatitis C can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of prevention efforts and identify missed opportunities for prevention, efforts are underway to help states establish and improve surveillance. HIV Infection, Adult* During 2000, a total of 21,704 cases of HIV infection (in the absence of AIDS diagnosis) in persons aged >13 years were reported. The number of reported cases of HIV infection is affected by epidemic trends as well as other factors (e.g., testing rates among populations at risk or when states initiated HIV case reporting). Before 1991, surveillance for HIV infection was not standardized, and reporting was primarily passive. CDC has since helped states conduct active surveillance for HIV infection using standardized report forms and software. In December 1999, CDC published a revised HIV case definition (effective January 2000) for adults and children aged >18 months that includes laboratory criteria requiring positive HIV antibody test results or reports of a detectable quantity of HIV nucleic acid or plasma HIV RNA (1). As states have begun implementing laboratory-initiated reporting of viral load tests, they have identified additional HIV and AIDS cases. HIV infection data should be interpreted with caution because not all infected persons have been tested and not all anonymous tests have been reported (2). Many factors influence testing patterns, including the extent that testing is targeted or routinely offered to specific groups and the availability of and access to medical care and testing services. To provide better data for HIV prevention, CDC and CSTE recommend that national surveillance include both HIV infection and AIDS (1,3). An integrated national HIV/AIDS surveillance system would provide information regarding persons in whom HIV infection has been newly diagnosed, those with severe HIV disease (i.e., AIDS), and those dying of HIV disease.

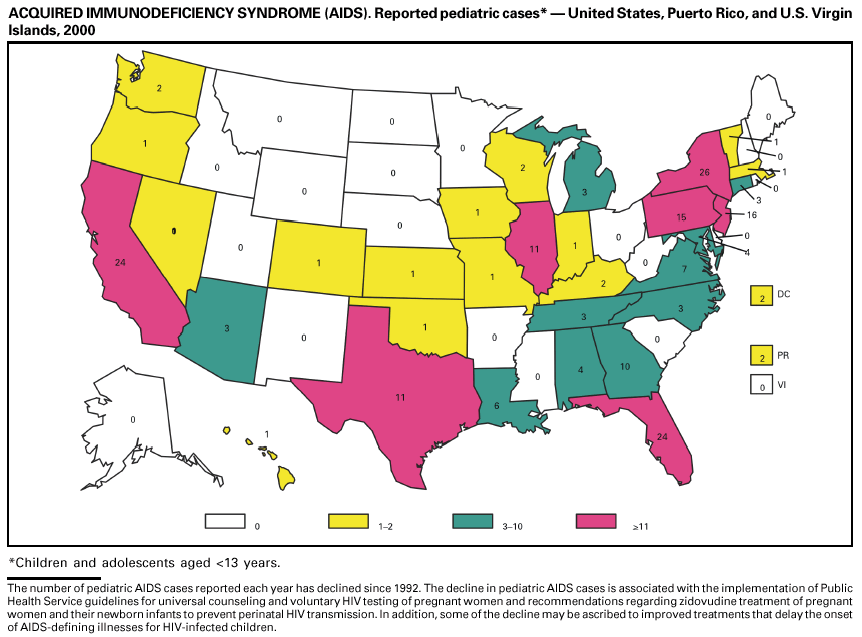

____________________ As of December 31, 2000, all states and U.S. territories reported AIDS in children aged <13 years, and 34 states and two territories also conducted surveillance for HIV infection among children. During 2000, a total of 224 children whose HIV infection had not progressed to AIDS and 196 children who had AIDS were reported. Data for 2000 indicated continued declines in perinatally acquired AIDS, reflecting declines in perinatal HIV transmission (1). The increasing use of zidovudine (ZDV) by mothers and newborns was temporally associated with this decline, demonstrating success in nationwide efforts to implement guidelines for routine, voluntary prenatal HIV testing (2) and the use of ZDV to reduce perinatal HIV transmission (3). Beginning January 1, 2000, the surveillance case definition for HIV infection was revised to reflect advances in laboratory HIV virologic tests and to incorporate the reporting criteria for HIV infection and AIDS into one case definition for adults and children (4). For children aged >18 months, the definition includes laboratory criteria requiring positive HIV antibody test results or reports of a detectable quantity of HIV nucleic acid or plasma HIV RNA (4). For children aged <18 months, the reporting criteria permit diagnosis of HIV infection during the first month of life. Children aged <18 months born to an HIV-infected mother are categorized as having perinatal exposure to HIV infection if they do not meet the criteria for either "HIV infection" or "not infected with HIV" (4,5).

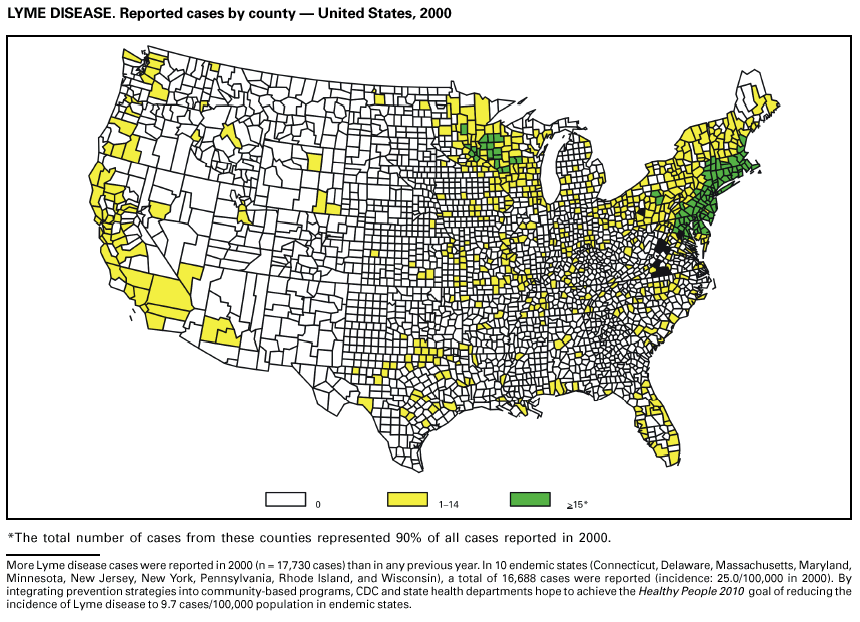

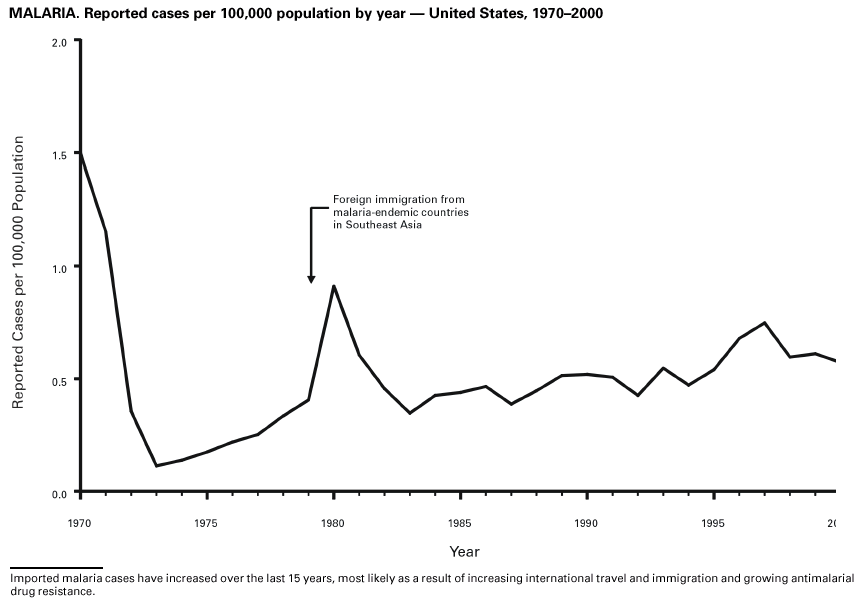

Lyme Disease During 2000, approximately 17,730 cases of Lyme disease were reported, most from the northeastern and north-central United States. CDC promotes community-based Lyme disease prevention using strategies aimed at reducing vector tick densities, preventing human exposure to infected vector ticks, and vaccinating persons aged 15--70 years when appropriate (1). CDC has funded new community-based prevention projects in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and New York. Malaria During 2000, a total of 1,560 malaria cases were reported in the United States. Most cases were imported, with approximately half occurring among U.S. residents traveling to malarious areas and half occurring among foreign residents immigrating to or visiting the United States (1). Although the number of reported cases was similar to 1999 (1,666) (2), the annual number of cases has increased during the past 15 years. This increase was likely caused by increases in both international travel (3) and immigration (4), as well as the spread and intensification of antimalarial drug resistance globally (5).

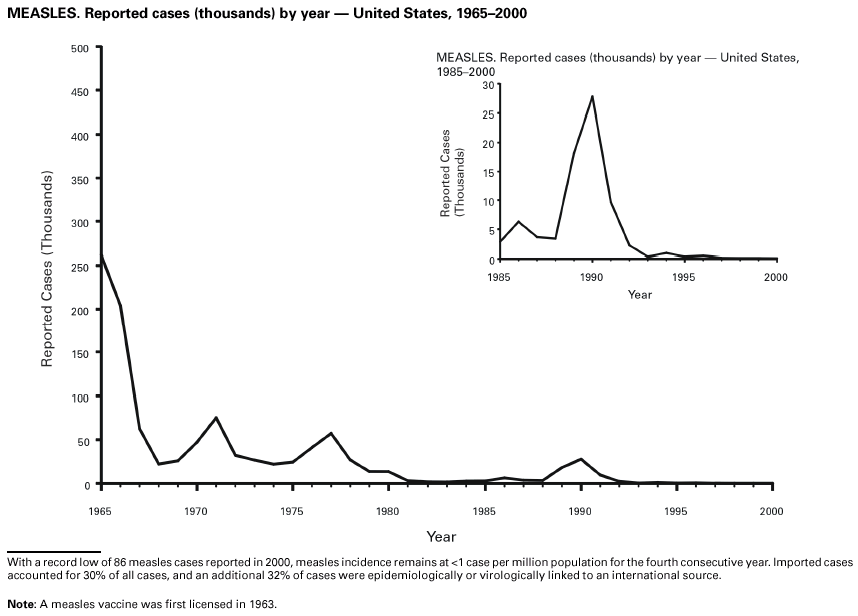

Measles During 2000, a total of 86 confirmed measles cases were reported. Thirty states and the District of Columbia did not report any confirmed cases. Thirty-seven case-patients were aged <5 years, 17 were aged 5--19 years, and 32 were aged >20 years. Ten outbreaks (range: 3--9 cases) were reported. Of the 86 cases reported, 26 were imported from outside the United States, and 19 cases were epidemiologically linked to imported cases. Nine additional cases had virologic evidence of importation (i.e., genotypic analysis of measles viruses indicated no evidence of an endemic strain). The remaining 32 cases were classified as unknown source cases because no link to importation was detected. Meningococcal Disease Rates of meningococcal disease have been relatively stable in the United States. A total of 2,256 cases were reported in 2000, of which 1,808 were confirmed, 111 probable, seven suspect, and 330 of unknown case status. Serogroup information was reported for 32% of cases, and serogroup Y accounted for 31% of those reported. Most other cases were caused by serogroup C (30%) or serogroup B (28%). Although rates of meningococcal disease are usually highest among children aged <1 year, 55% of cases in 2000 occurred among persons aged >18 years. Using the technology applied to the development of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) conjugate vaccines, several companies are in the final stages of developing and testing meningococcal conjugate vaccines with various serogroup-specific formulas and in combination with other antigens for licensure in the United States (1). Three serogroup C meningococcal conjugate vaccines were licensed and integrated into routine childhood immunization in the United Kingdom last year; early results confirm >90% efficacy in toddlers and teenagers (2).

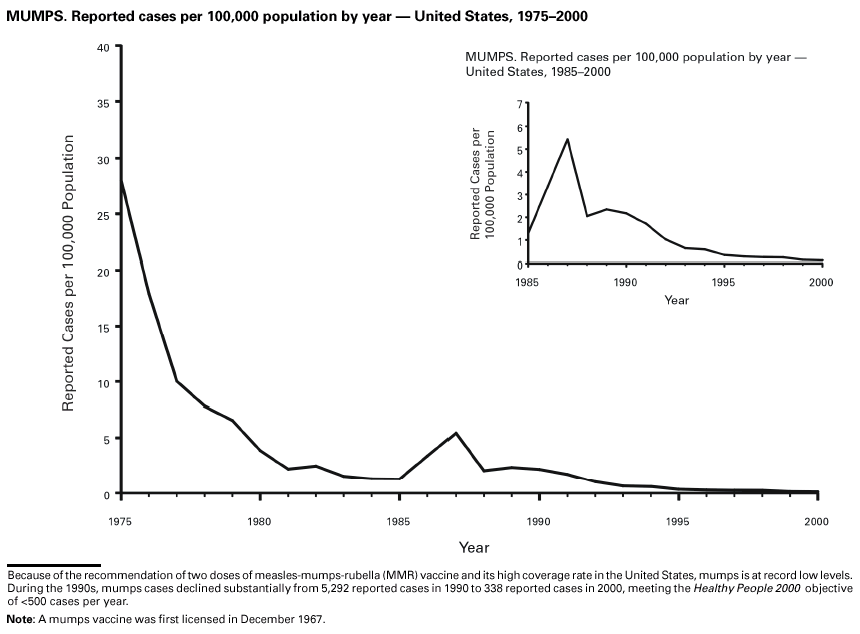

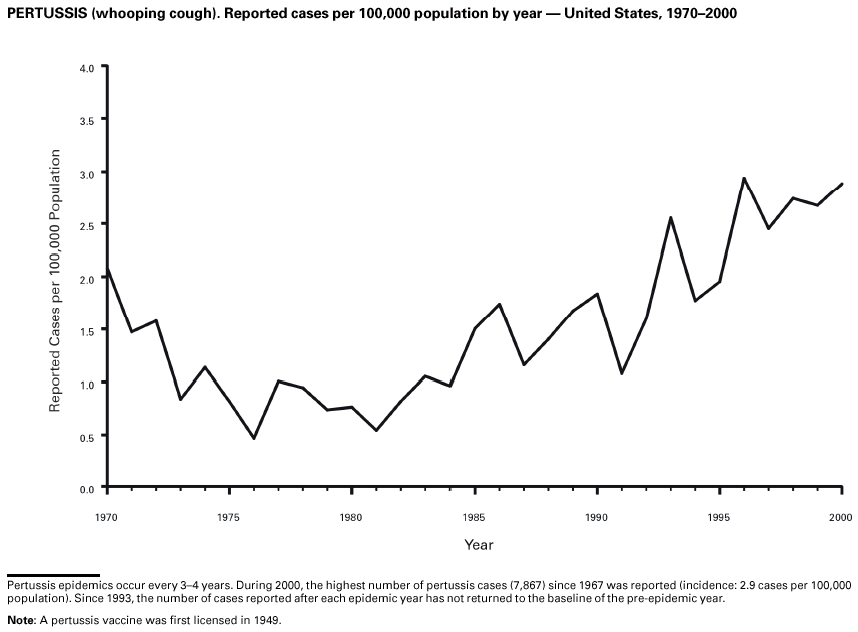

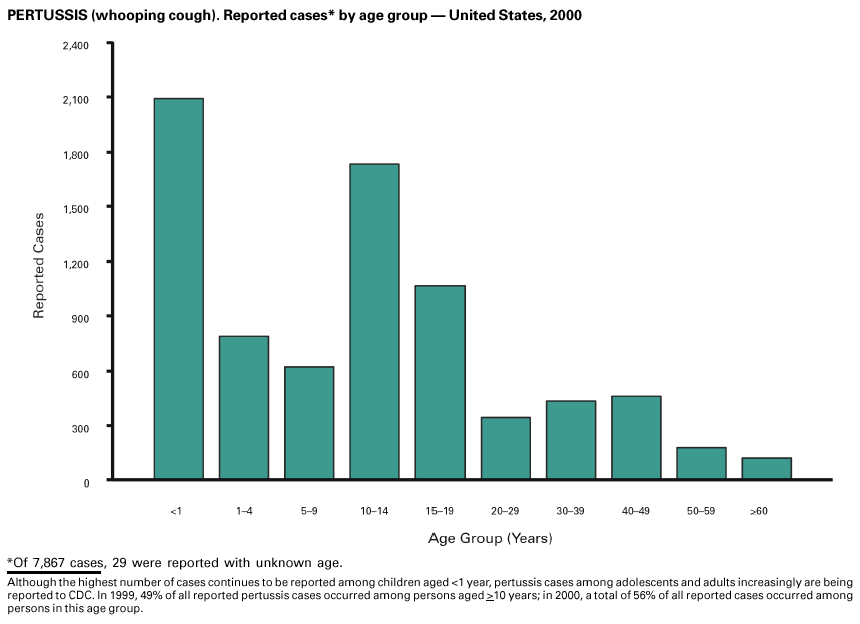

Mumps Because of the recommendation of two doses of MMR and its high coverage rate in the United States, mumps is at record low levels. During the 1990s, mumps cases declined substantially, from 5,292 reported cases in 1990 to 338 reported cases in 2000, meeting the Healthy People 2000 objective of <500 cases per year (1). Pertussis During 2000, a total of 7,867 cases of pertussis were reported. Of these cases, 24% occurred among children too young to have received the recommended three doses of a pertussis-containing vaccine (i.e., those aged <7 months); 2% among children aged 7--11 months; 10% among preschool-aged children (aged 1--4 years); 8% among children aged 5--9 years; 36% among persons aged 10--19 years; and 20% among persons aged >20 years. Since 1995, the coverage rate with >3 doses of a pertussis-containing vaccine has been 95% among U.S. children aged 19--35 months (1). Since 1990, the incidence of pertussis among preschool-aged children has not changed, but the incidence among adolescents has increased in some states (2). Because vaccine-induced immunity wanes approximately 5--10 years after pertussis vaccination, adolescents can become susceptible to disease. Pertussis deaths reported through NNDSS also increased in the 1990s, predominantly among infants too young to receive three doses (CDC, unpublished data, 2000). Since 1980, the number of reported pertussis cases has increased in the United States (2). The reasons are unknown but could include increased awareness of pertussis among health-care providers, increased use of more sensitive diagnostic tests, better reporting of cases to health departments, and an increase in circulating pertussis.

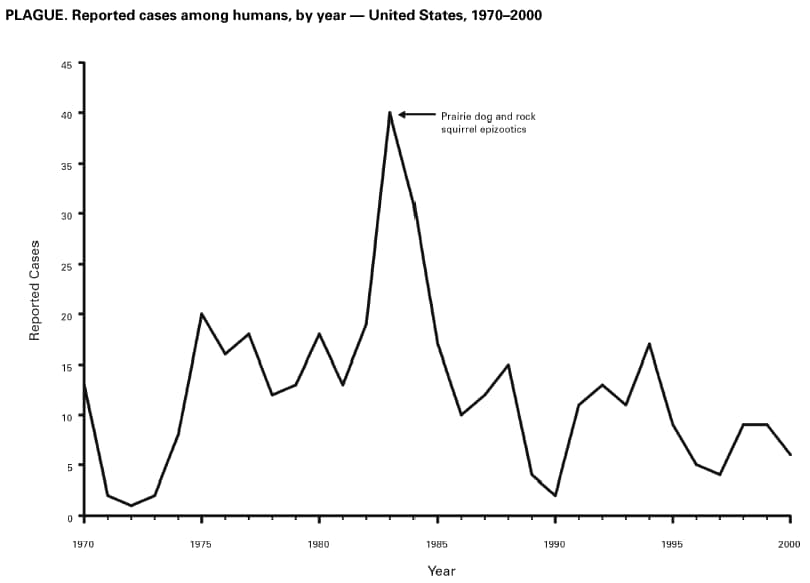

Plague During 2000, six cases of human plague were reported from six states (Arizona, California, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming), representing <50% of the average number reported during the past 20 years (i.e., 13.1 cases/year during 1980--1999). None of the six cases were fatal, and all were acquired from naturally occurring sources. The low number of reported cases is possibly linked to hot summer and dry winter conditions during the past 2 years in the southwestern states of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah (1,2). CDC works cooperatively with state and local health departments and other federal agencies to improve human and animal-based plague surveillance programs, including the ability to detect human cases acquired from natural sources or as a result of bioterrorism. In 2000, these efforts included CDC participation in a bioterrorism exercise designed to test the abilities of public health and other agencies to respond to a large pneumonic plague outbreak caused by an aerosol release of Yersinia pestis in a major U.S. city (Denver) (3). The exercise highlighted the need for an improved understanding of concerns related to leadership, decision-making, prioritization and distribution of resources, formulation of appropriate principles for containment, and development of methods for managing the crises that would occur in health-care facilities during such an incident.

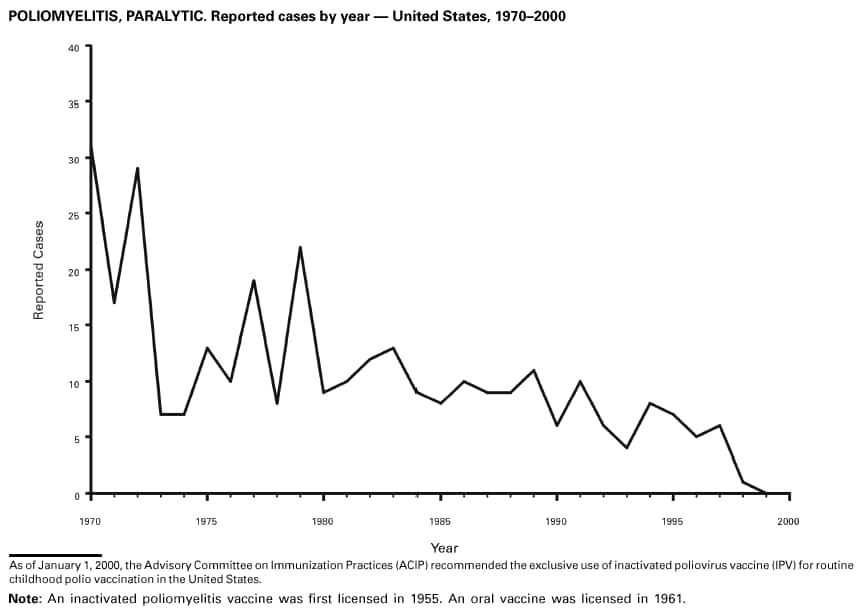

Poliomyelitis, Paralytic In January 2000, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) approved an all inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) schedule for routine childhood vaccination to eliminate the risk for vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) (1). Since implementation of this schedule, no cases of VAPP have been confirmed in the United States. Continued monitoring with additional observation time is required to confirm these preliminary findings because of potential delays in reporting. Under the previous schedule of all oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV), which ended in 1997, an average eight VAPP cases were reported each year (2). Under the sequential polio vaccine schedule (two doses of IPV followed by two doses of OPV) used during 1997--1999, the number of VAPP cases declined steadily from seven cases in 1997 to two cases each in 1998 and 1999 (3).

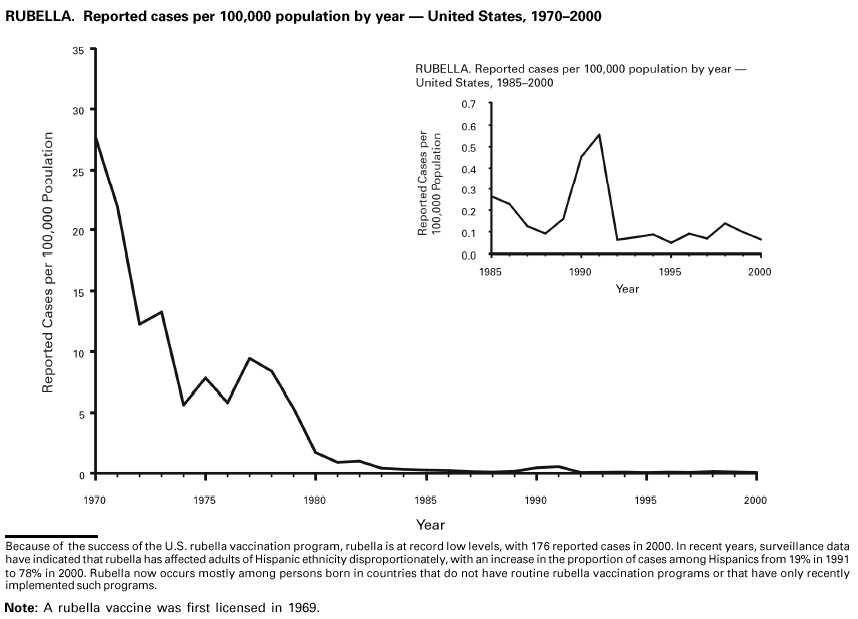

Rubella Because of the success of the U.S. rubella vaccination program, rubella is at a record low level, with 176 reported cases in 2000. In recent years, surveillance data have indicated that rubella has disproportionately affected adults of Hispanic ethnicity, with an increase in the proportion of cases among Hispanics from 19% in 1991 to 78% in 2000. Rubella now mostly occurs among persons born in countries that do not have routine rubella vaccination programs or that have only recently implemented such programs.

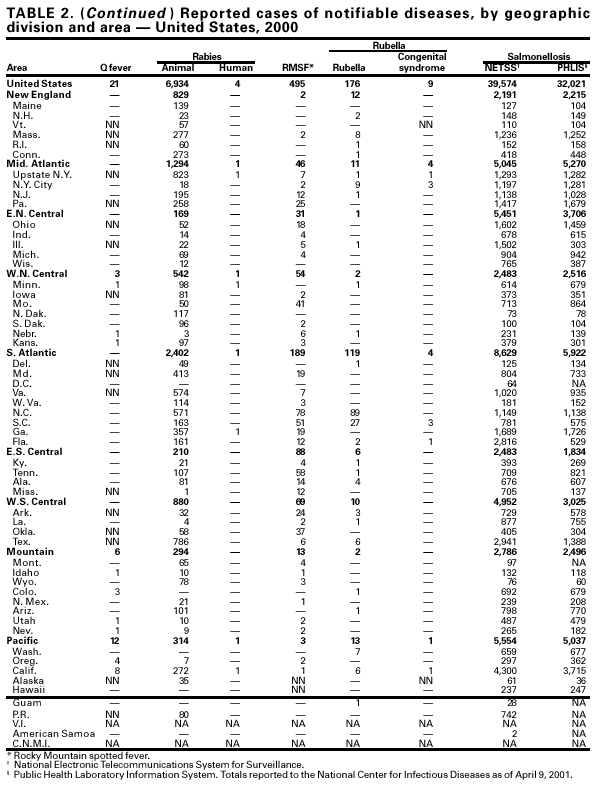

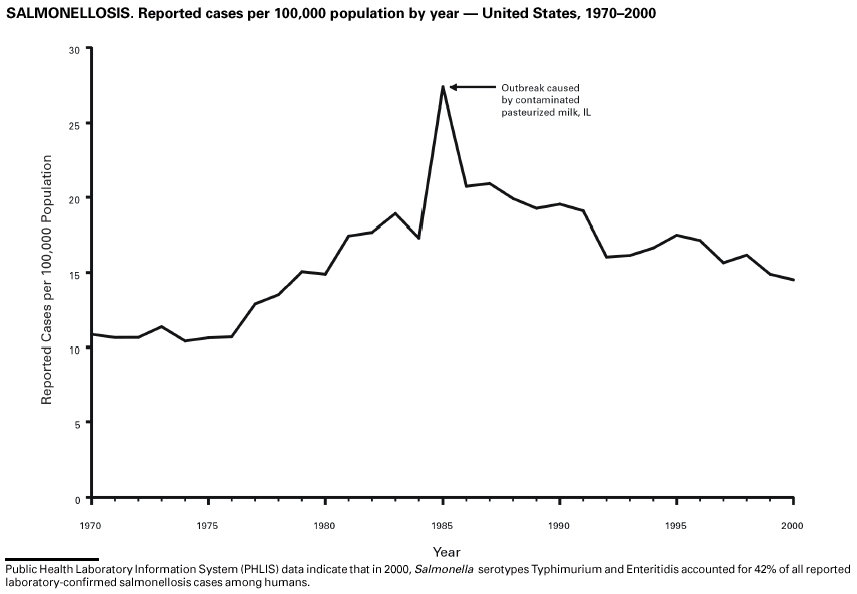

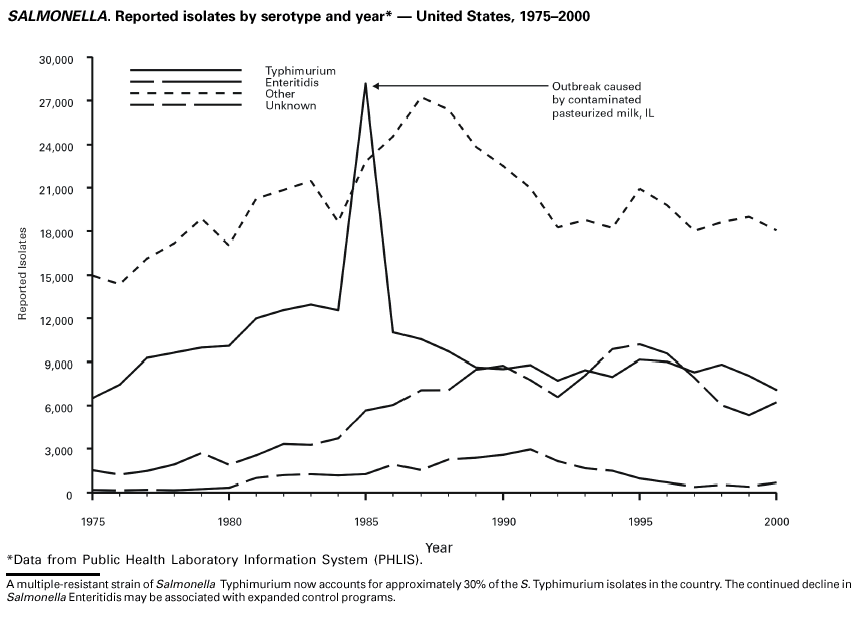

Salmonellosis During 2000, a total of 32,021 Salmonella isolates were reported through the Public Health Laboratory Information System (PHLIS) (rate: 11.7/100,000), which was a 24% decrease from 1990 and a 2% decrease from 1999. Of the 2,449 known Salmonella serotypes, the two most commonly reported in 2000 were Typhimurium and Enteritidis, accounting for 42% of isolates. S. Typhimurium and S. Enteritidis have ranked first and second, respectively, in frequency since 1990, although their rankings reversed during 19941996 (1). According to a 1999 national survey, 49% of S. Typhimuriumisolates were resistant to more than one drug, and 28% had a five-drug resistance pattern characteristic of a single phage type, Definitive Type 104 (2). The number of reported S. Enteritidis isolates has decreased since the mid-1990s, possibly because of egg safety regulations and egg industry improvements in the 1990s (3).

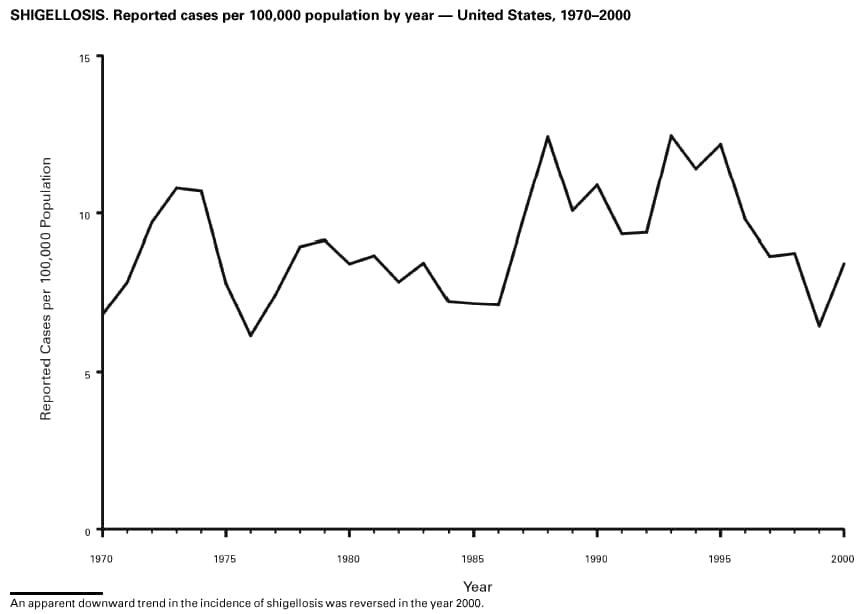

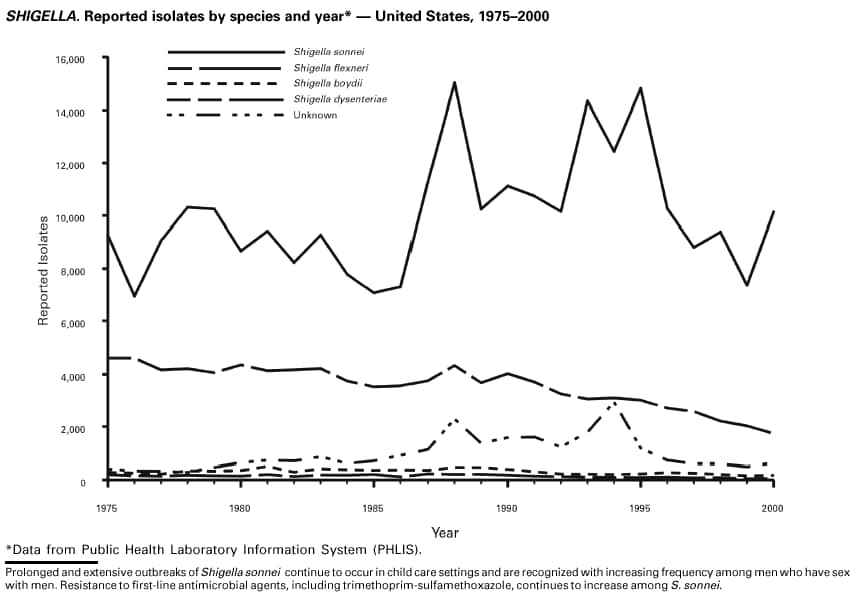

Shigellosis During 2000, a total of 12,732 isolates of shigellosis were reported through PHLIS, with Shigella sonnei infections continuing to account for most cases in the United States. Prolonged, communitywide outbreaks of S. sonnei infections transmitted in child care centers and other settings where maintenance of good hygienic conditions requires special care account for much of the problem (1). S. sonnei also can be transmitted through contaminated foods and water used for drinking or recreational purposes (2,3), and recent evidence has indicated that infections are increasing among men who have sex with men (4).

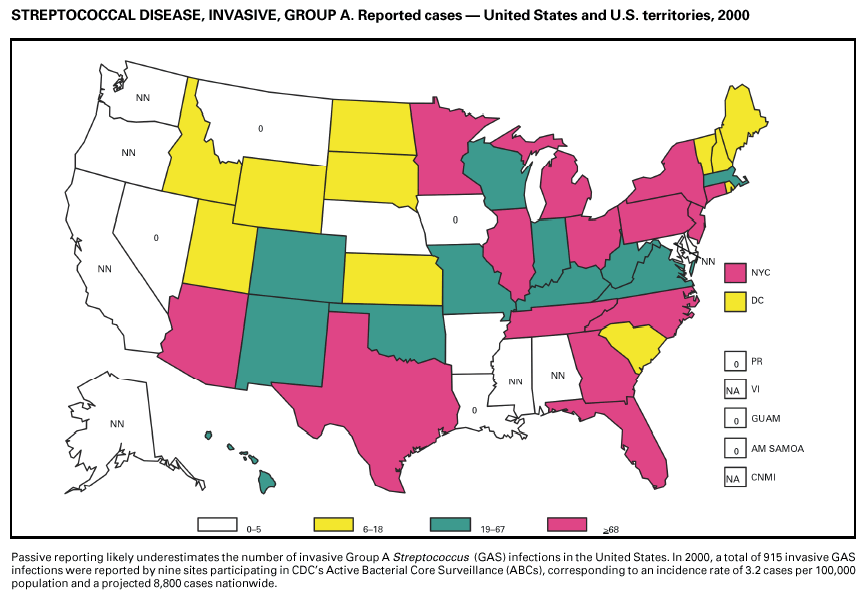

Streptococcal Disease, Invasive, Group A (including streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome) During 2000, a total of 915 cases of invasive group A streptococcal (GAS) disease were reported from nine states (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, and Tennessee) through the Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) project under CDC's Emerging Infections Program (1). Based on these 915 cases, CDC estimates that approximately 8,800 cases of invasive GAS disease (rate: 3.2/100,000) and 1,000 deaths occurred nationally during 2000. Disease incidence was highest among children aged 1 year (5.8/100,000) and adults aged >65 years (8.5/100,000). Streptococcal toxic-shock syndrome and necrotizing fasciitis accounted for approximately 4.0% and 6.0% of invasive cases, respectively. The overall case-fatality rate among patients with invasive GAS disease was 11.5%. CDC identifies invasive GAS isolates based on sequences of the variable portion of the M-protein gene (i.e., emm typing). Although approximately 50% of the GAS isolates emm-typed for 2000 were one of the five known emm types (i.e., 1, 3, 12, 28, and 82), emm-type distribution shows considerable geographic diversity.

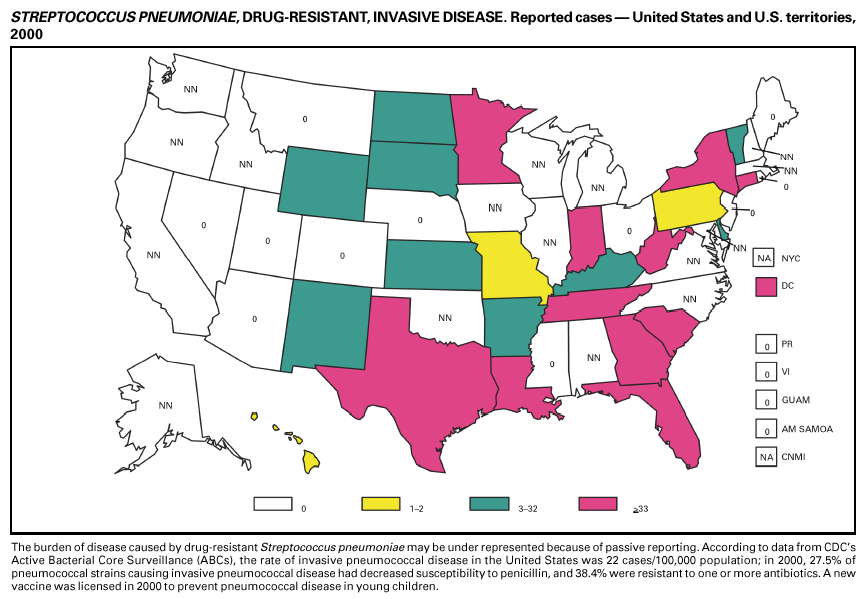

Streptococcus pneumoniae, Drug-Resistant, Invasive Disease During 2000, CDC collected information on invasive pneumococcal disease, including drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, in nine states (California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Maryland, Minnesota, New York, Oregon, and Tennessee) (1). Of the 3,607 S. pneumoniae isolates collected, 9.8% exhibited intermediate resistance to penicillin (minimum inhibitory concentration [MIC] of 0.1--1 µg/mL), and 17.1% were fully resistant (MIC >2 µg/mL) (2). For cefotaxime, 9.8% of all isolates had intermediate resistance and 7.5% were resistant. For erythromycin, 21.3% were resistant. Approximately one-fifth (18.9%) of isolates were not susceptible to the three classes of drugs commonly used to treat pneumococcal infections. In February 2000, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) licensed a pneumococcal conjugate vaccine for use in infants and young children. In October 2000, ACIP issued recommendations for use of the vaccine in children aged <5 years (3). Of isolates from children aged <5 years reported during 2000, a total of 67.6% of all strains (n = 887) and 77.7% of strains not susceptible to penicillin (n = 328) were serotypes included in this 7-valent vaccine.

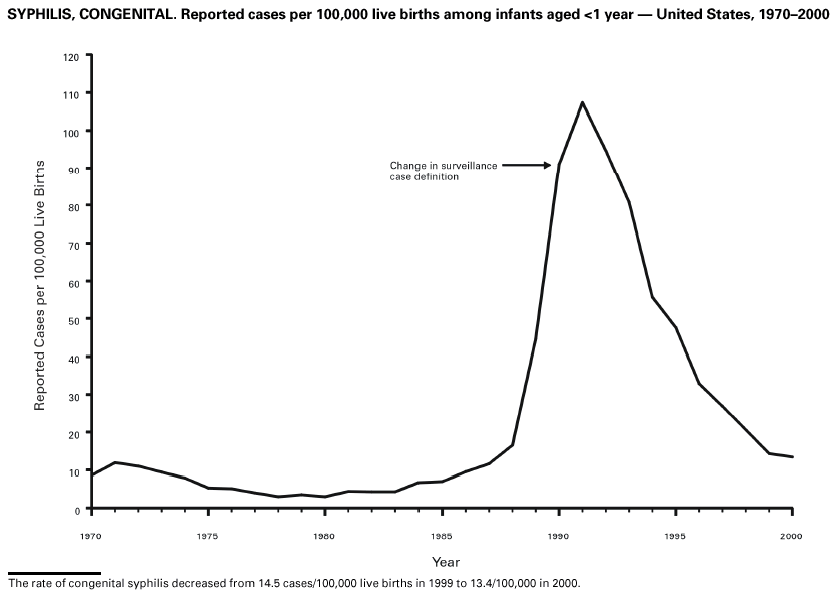

Syphilis, Congenital During 2000, a total of 529 cases of congenital syphilis were reported (rate: 12.6/100,000 live births). Like primary and secondary syphilis, the rate of congenital syphilis has declined sharply in recent years, from a peak of 107.3/100,000 in 1991 (1). Congenital syphilis persists in the United States because a substantial number of women do not receive syphilis serologic testing until late in their pregnancy or not at all. This lack of screening is often related to absent or late prenatal care (2).

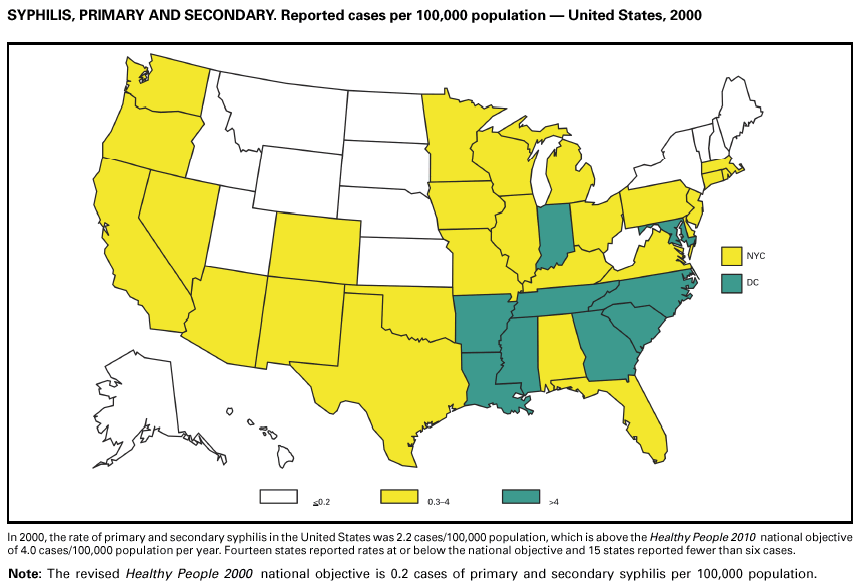

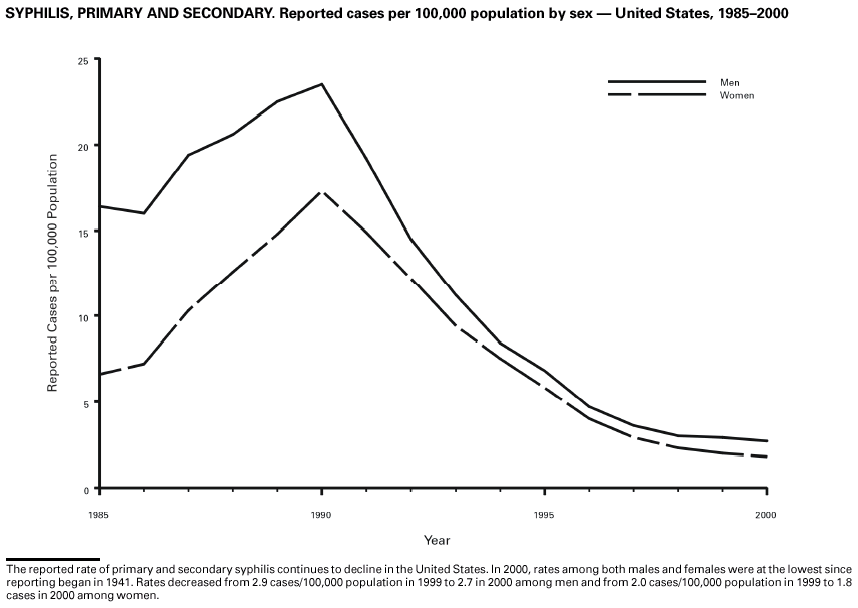

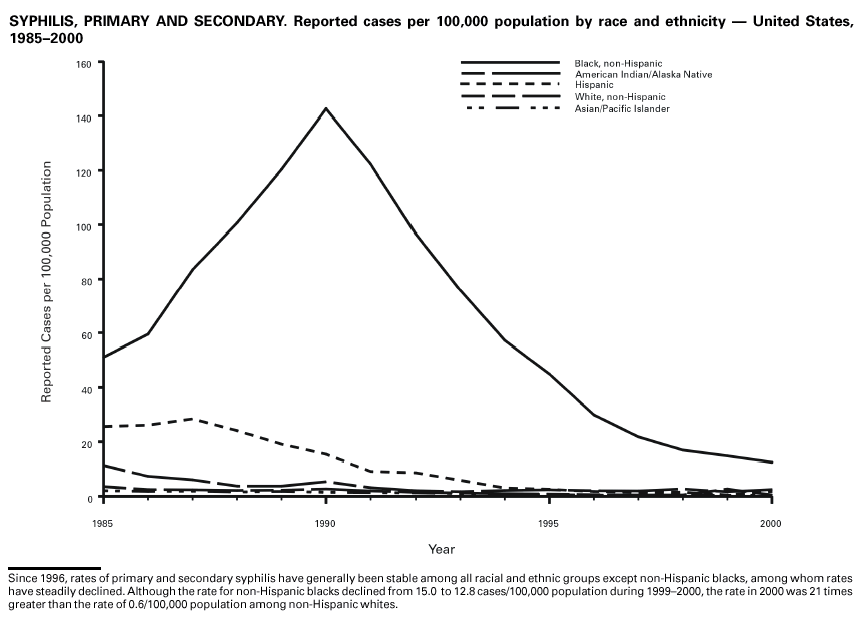

Syphilis, Primary and Secondary During 2000, a total of 5,979 primary and secondary syphilis cases were reported. During 19902000, the primary and secondary syphilis rate declined 89%, from 20.3/100,000 to 2.2/100,000. The 2000 rate was the lowest since reporting began in 1941 (1). Although syphilis has declined in all regions of the United States and in all racial/ethnic groups, rates remain disproportionately high in the South and among non-Hispanic blacks, and focal outbreaks continue to occur (including recent outbreaks among men who have sex with men [2,3]).

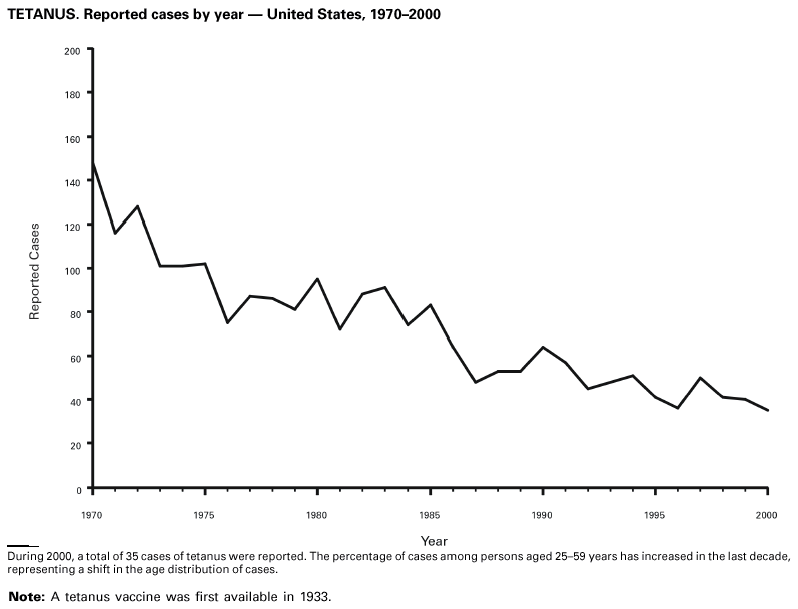

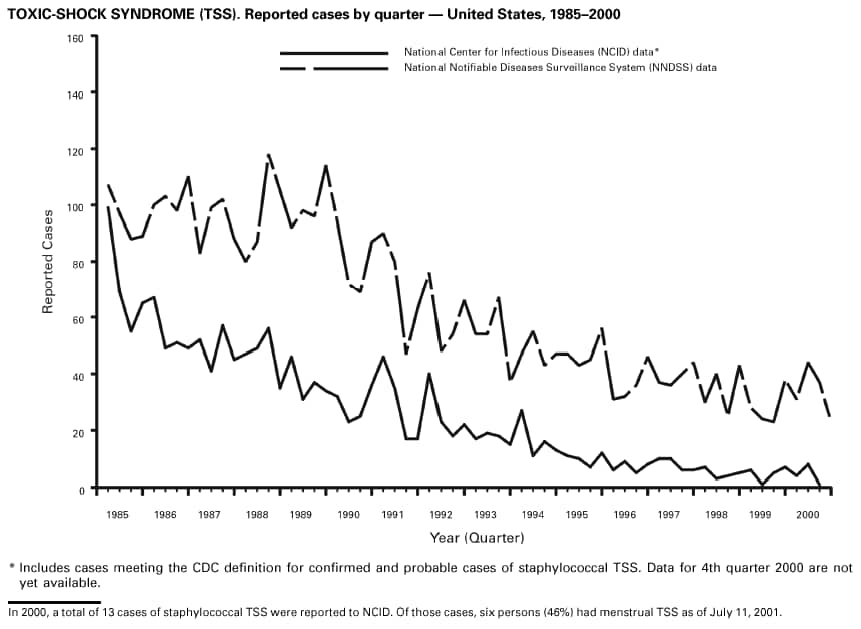

Tetanus During 2000, a total of 35 cases of tetanus were reported from 19 states; no cases of neonatal tetanus were reported. Four (11%) cases were among persons aged <25 years, 19 (54%) among persons aged 25--59 years, and 12 (34%) among persons aged >59 years. The percentage of cases among persons aged 25--59 years has increased during the 1990s; previously, most cases were among persons aged >59 years (1). One case occurred in a child aged 12 years who had never been vaccinated against tetanus because of the parents' objection to vaccination. Six (15%) cases were fatal. Toxic-Shock Syndrome During 2000, a total of 135 cases of toxic-shock syndrome (TSS) were reported. Of these cases, three occurred in men. Three cases were fatal, with two of the deaths menstruation-related. The limited number of reported cases in recent years is likely caused by decreased reporting and not a true decline in incidence of disease (1). Continued surveillance will be important to monitor the reemergence of TSS that could occur among women using barrier contraceptive devices and to define better the risk factors for nonmenstrual TSS.

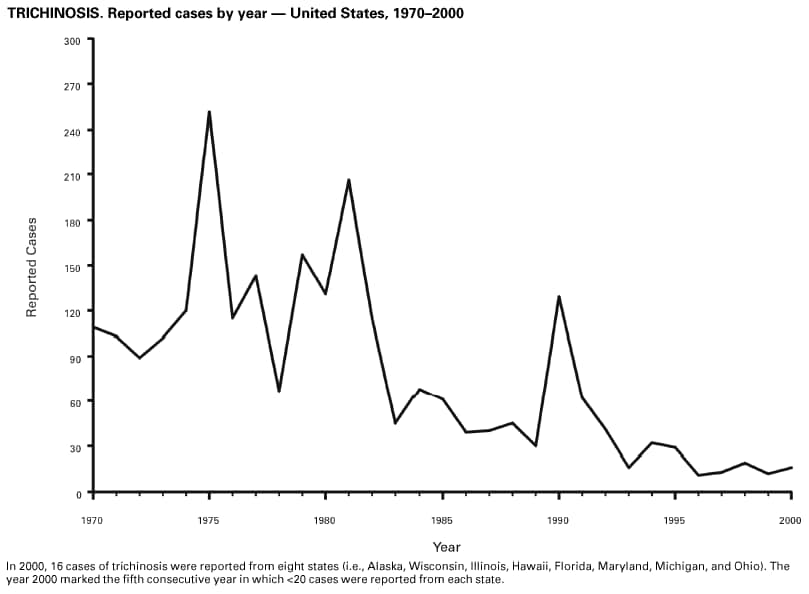

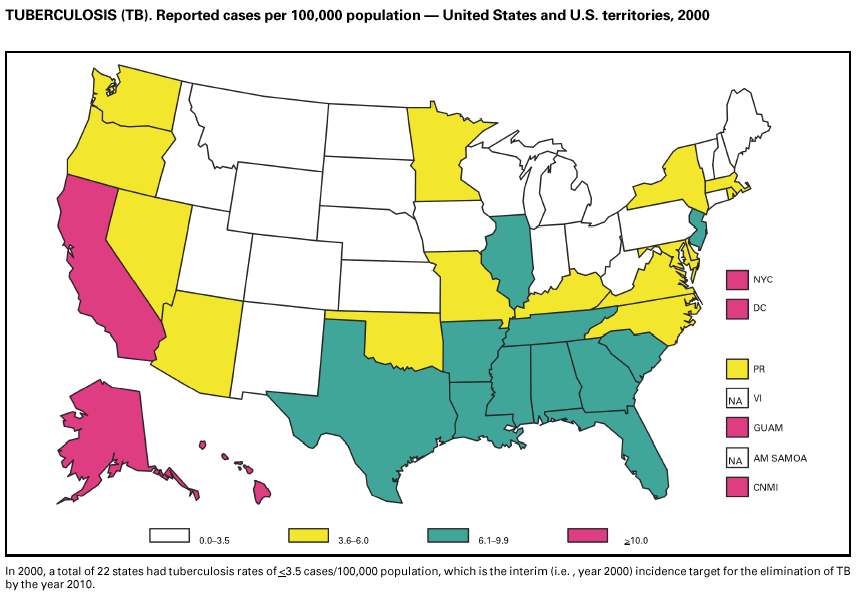

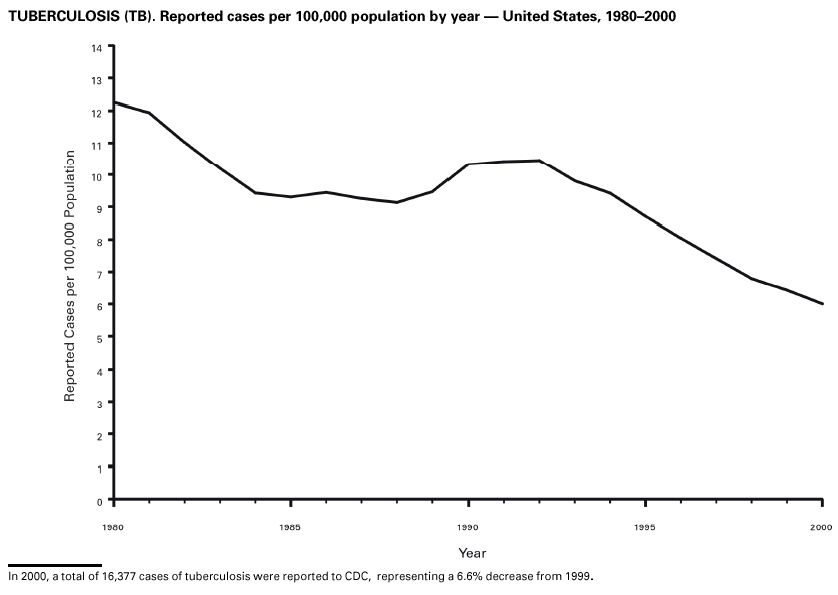

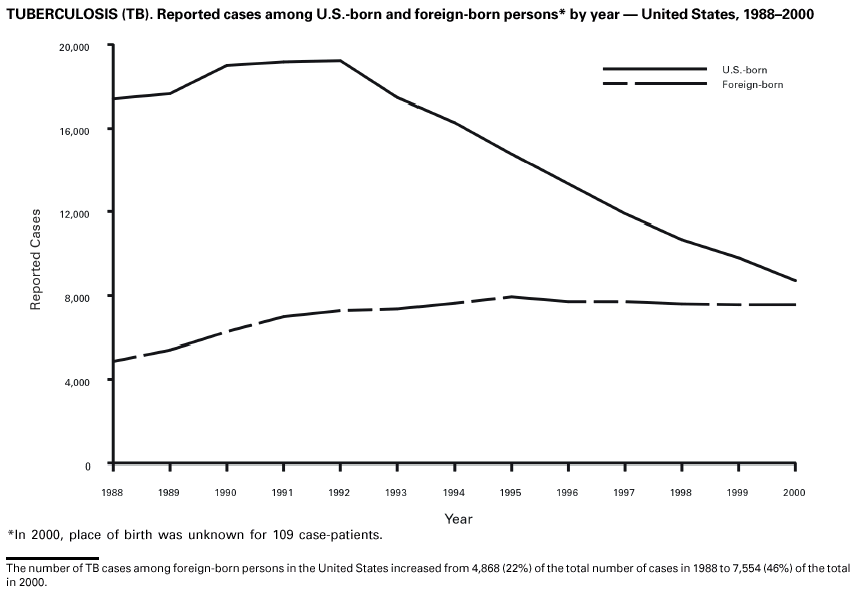

Trichinosis During 2000, a total of 16 cases of trichinosis were reported from eight states (Alaska, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Michigan, Ohio, and Wisconsin). Case-patients included seven men and three women whose ages ranged from 34 to 65 years. Bear meat was the cause of the five cases reported from Alaska, and pork was identified as the source of cases from Illinois (n = 2) and Hawaii (n = 1). Tuberculosis During 2000, a total of 16,377 tuberculosis (TB) cases (rate: 6.0/100,000) were reported (1), representing a 7% decrease from 1999 and a 39% decrease from 1992, when cases peaked during the resurgence of TB in the United States. During 1992--2000, TB cases among U.S.-born persons decreased 55%, whereas cases among foreign-born persons increased 4% (1). Since 1993, when states began reporting initial drug susceptibility results to CDC, the number of multidrug-resistant TB (MDR TB) cases in persons with no previous history of TB decreased from approximately 400 (2.5%) to approximately 120 (1.1%) (1). These declines could be the result of stronger control efforts after the resurgence of TB and the emergence of MDR TB. The relatively stable number of cases reported among foreign-born persons indicates that most cases could be caused by infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the person's country of origin. CDC has collaborated with state and local health departments to publish recommendations for enhancing TB control efforts among foreign-born persons and is working to expand current efforts based on these recommendations (2,3).

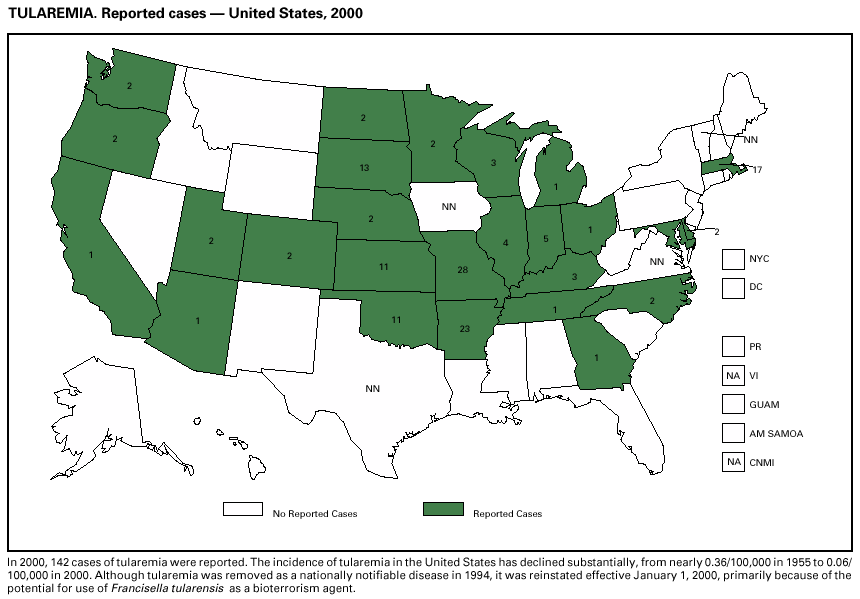

Tularemia During 2000, a total of 142 cases of tularemia were reported. The incidence of tularemia in the United States has declined substantially, from nearly 0.36/100,000 in 1955 to 0.06/100,000 in 2000 (1). Although tularemia was removed as a nationally notifiable disease in 1994, it was reinstated effective January 1, 2000, primarily because of the potential for use of Francisella tularensis as a bioterrorism agent (2). Guidelines for public health and medical response to the use of F. tularensis as a biological weapon are available (3). During the summer of 2000, lawn mowing or brush-cutting was identified as a risk factor in an outbreak of pneumonic tularemia on Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts (4).

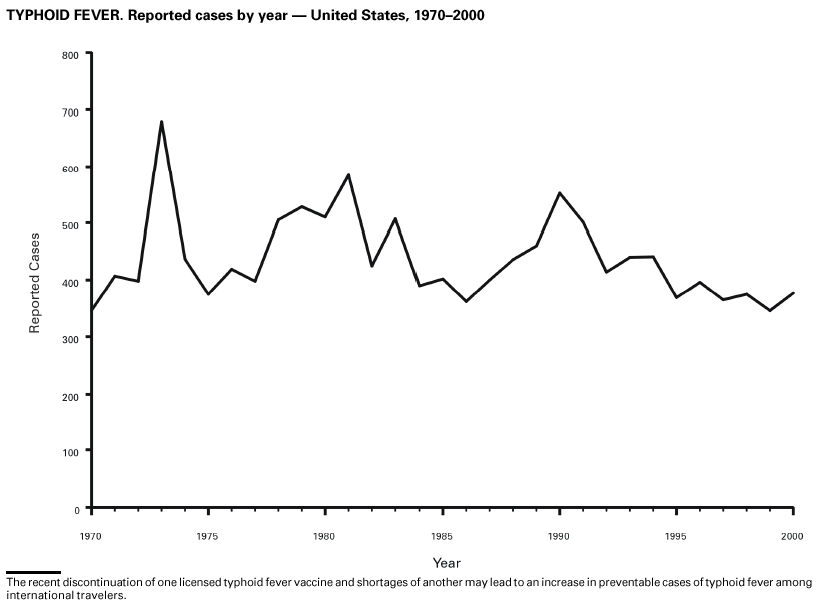

Typhoid Fever During 2000, a total of 377 cases of typhoid fever were reported. Despite the availability of two effective vaccines, 300--400 cases are reported each year. Approximately 80% of these cases occur in persons who report international travel during the 6 weeks before illness. Persons traveling to and from their country of origin can be at high risk (1). In many areas of the world, Salmonella Typhi strains have acquired resistance to multiple antimicrobial agents, including ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (1).

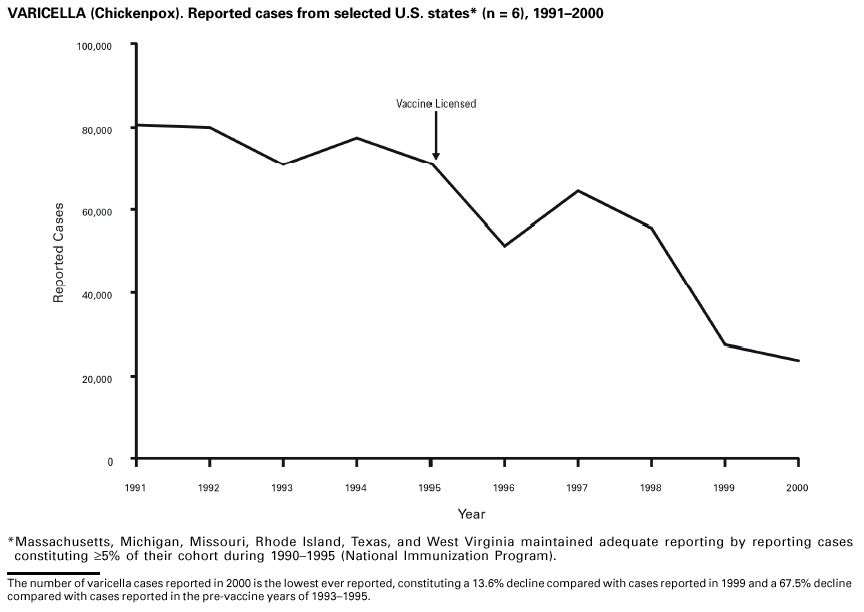

Varicella In 1995, varicella vaccine was licensed in the United States, and in 1996, the vaccine became available for use in the public sector (1). Although varicella is not a nationally notifiable disease, since 1990, six states (Massachusetts, Michigan, Missouri, Rhode Island, Texas, and West Virginia) have maintained adequate reporting levels by reporting varicella disease burden constituting >5% of their birth cohort.* In these states, a 67% reduction in disease incidence has occurred between the immediate prevaccination years (1993--1995) and the most recent year for which data are available (2000). This decrease is associated with rapidly increasing vaccination coverage; among children aged 19--35 months, vaccination coverage reached 63% during July 1999--June 2000. The marked decline in reported cases from passive reporting to CDC was consistent with data from active varicella surveillance sites (CDC, unpublished data, 2000). Ongoing surveillance will be important to monitor the impact of the varicella vaccination program. Although deaths from varicella became nationally notifiable beginning January 1, 1999, reporting remains incomplete (2). CDC encourages all states to review death certificates and vital statistics to identify and report deaths from varicella among children, adolescents, and adults.

____________________ PART 1Summaries of Notifiable Diseases in the United States, 2000

PART 2Graphs and Maps for Selected Notifiable Diseases in the United States

PART 3Historical Summaries of Notifiable Diseases in the United States, 1969–2000

Selected ReadingGeneralBayer R, Fairchild AL. Public health: surveillance and privacy. Science 2000;290:1898--9. Chin JE, ed. Control of communicable diseases manual. 17th ed. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2000. Freimuth V, Linnan HW, Potter P. Communicating the threat of emerging infections to the public. Emerg Infect Dis 2000;6:337--47. Lin SS, Kelsey JL. Use of race and ethnicity in epidemiologic research: concepts, methodological issues, and suggestions for research. Epidemiol Rev 2000;22:187--202. Pinner RW, Jernigan DB, Sutliff SM. Electronic laboratory-based reporting for public health. Military Medicine 2000;165(suppl 2):20--4. Pinner RW, Koo D, Berkelman RL. Surveillance of infectious diseases. In: Lederberg J, Alexander M, Bloom RB, eds. Encyclopedia of microbiology. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 2000;4:506--25. Teutsch SM, Churchill RE, eds. Principles and practice of public health surveillance. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2000. CDC. Framework for program evaluation in public health. MMWR 1999;48(No. RR11). CDC. Manual for the surveillance of vaccine preventable diseases. Atlanta, GA: CDC, 1999. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/nip/publications/survmanual/begin.pdf>. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 1998. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC, 1999. Effler P, ChingLee M, Bogard A, Ieong MC, Nekomoto T, Jernigan D. Statewide system of electronic notifiable disease reporting from clinical laboratories: comparing automated reporting with conventional methods. JAMA 1999;282:1845--50. Abstract available at <http://jama.amaassn.org/issues/v282n19/abs/joc90534.html>. Koo D, Caldwell B. The role of providers and health plans in infectious disease surveillance. Eff Clin Pract 1999;2:247--52. Available at <http://www.acponline.org/journals/ecp/sepoct99/koo.htm>. Roush S, Birkhead G, Koo D, Cobb A, Fleming D. Mandatory reporting of diseases and conditions by health care professionals and laboratories. JAMA 1999;282:164--70. Available at <http://jama.amaassn.org/issues/v282n2/abs/joc90413.html>. Niskar AS, Koo D. Differences in notifiable infectious disease morbidity among adult women---United States, 1992--1994. J Womens Health 1998;7:451--8. Koo D, Wetterhall S. History and current status of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. J Public Health Manag Pract 1996;2:4--10. CDC. Manual of procedures for the reporting of nationally notifiable diseases to CDC. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC, 1995. Martin SM, Bean NH. Data management issues for emerging diseases and new tools for managing surveillance and laboratory data. Emerg Infect Dis 1995;1:124--8. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol1no4/martin2.htm#top>. Thacker SB, Stroup DF. Future directions for comprehensive public health surveillance and health information systems in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 1994;140:383--97. CDC. Proceedings of the 1992 International Symposium on Public Health Surveillance. MMWR 1992;41(suppl). Thacker SB, Choi K, Brachman PS. The surveillance of infectious diseases. JAMA 1983;249:1181--5. AIDSCDC. HIV and AIDS---United States, 1981--2000. MMWR 2001;50:430--4. Karon JM, Fleming PL, Steketee RW, De Cock KM. HIV in the United States at the turn of the century: an epidemic in transition. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1060--8. BotulismAngulo FJ, Getz J, Taylor JP, et al. A large outbreak of botulism: the hazardous baked potato. J Infect Dis 1998;178:172--7. CDC. Botulism in the United States, 1899--1996: handbook for epidemiologists, clinicians, and laboratory workers. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, CDC, 1998. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/diseaseinfo/botulism.pdf>. Shapiro RL, Hatheway C, Becher J, Swerdlow D. Botulism surveillance and emergency response: a public health strategy for a global challenge. JAMA 1997;278:433--5. BrucellosisYagupsky P. Detection of brucellae in blood cultures. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:3437--42. CDC. Human exposure to Brucella abortus strain RB51---Kansas, 1997. MMWR 1998;47:172--5. Chomel BB, DeBess EE, Mangiamele DM, et al. Changing trends in the epidemiology of human brucellosis in California from 1973 to 1992: a shift toward foodborne transmission. J Infect Dis 1994;170:1216--23. Taylor JP, Perdue JN. The changing epidemiology of human brucellosis in Texas, 1977--1986. Am J Epidemiol 1989;130:160--5. ChancroidMertz KJ, Trees D, Levine WC, et al. Etiology of genital ulcers and prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus coinfection in 10 US cities. The Genital Ulcer Disease Surveillance Group. J Infect Dis 1998;178:1795--8. Mertz KJ, Weiss JB, Webb RM, et al. An investigation of genital ulcers in Jackson, Mississippi, with use of a multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay: high prevalence of chancroid and human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Infect Dis 1998;178:1060--6. DiCarlo RP, Armentor BS, Martin DH. Chancroid epidemiology in New Orleans men. J Infect Dis 1995;172:446--52. Chlamydia trachomatis, Genital infectionCDC. Chlamydia trachomatis genital infections---United States, 1995. MMWR 1997;46:193--8. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2000 supplement: Chlamydia Prevalence Monitoring Project. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, November 2001. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/std/chlamydia2001>. Gaydos CA, Howell MR, Pare B, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis infections in female military recruits. N Engl J Med 1998;339:739--44. Mertz KJ, McQuillan GM, Levine WC, et al. A pilot study of chlamydial infection in a national household survey. Sex Transm Dis 1998;25:225--8. CholeraMintz ED, Tauxe RV, Levine MM. The global resurgence of cholera. In: Noah ND, O'Mahony M, eds. Communicable disease epidemiology and control. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, 1998:63--104. Mahon BE, Mintz ED, Greene KD, Wells JG, Tauxe RV. Reported cholera in the United States, 1992--1994: a reflection of global changes in cholera epidemiology. JAMA 1996;276:307--12. Wachsmuth IK, Blake PA, Olsvik O, eds. Vibrio cholerae and cholera: molecular to global perspectives. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology, 1994. World Health Organization. Guidelines for cholera control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1993. CyclosporiasisLopez AS, Dodson DR, Arrowood MJ, et al. Outbreak of cyclosporiasis associated with basil in Missouri in 1999. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:1010--7. Herwaldt BL. Cyclospora cayetanensis: a review, focusing on the outbreaks of cyclosporiasis in the 1990s. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:1040--57. Herwaldt BL, Beach MJ. The return of Cyclospora in 1997: another outbreak of cyclosporiasis in North America associated with imported raspberries. Cyclospora Working Group. Ann Intern Med 1999;130:210--20. Herwaldt BL, Ackers ML. An outbreak in 1996 of cyclosporiasis associated with imported raspberries. The Cyclospora Working Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1548--56. DiphtheriaDittmann S, Wharton M, Vitek C, et al. Successful control of epidemic diphtheria in the states of the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics: lessons learned. J Infect Dis 2000;181 (suppl 1):S10--S22. Bisgard KM, Hardy IR, Popovic T, et al. Respiratory diphtheria in the United States, 1980 through 1995. Am J Public Health 1998;88:787--91. Galazka AM, Robertson SE. Diphtheria: changing patterns in the developing world and the industrialized world. European J Epidemiol 1995;11:107--17. Ehrlichiosis (Human Granulocytic and Human Monocytic)Belongia EA, Reed KD, Mitchell PD, et al. Tickborne infections as a cause of nonspecific febrile illness in Wisconsin. Clin Infect Dis 2001;32:1434--9. IJdo JW, Meek JI, Cartter ML, et al. The emergence of another tickborne infection in the 12-town area around Lyme, Connecticut: human granulocytic ehrlichiosis. J Infect Dis 2000;181:1388--93. Childs JE, Sumner JW, Nicholson WL, Massung RF, Standaert SM, Paddock CD. Outcome of diagnostic tests using samples from patients with culture-proven human monocytic ehrlichiosis: implications for surveillance. J Clin Microbiol 1999;37:2997--3000. McQuiston JH, Paddock CD, Holman RC, Childs JE. The human ehrlichioses in the United States [Review]. Emerg Infect Dis 1999;5:635--42. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol5no5/mcquiston.htm>. Encephalitis (California Serogroup Viral, Eastern Equine, St. Louis, Western Equine, West Nile)Escherechia coli O157:H7 Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, PostdiarrhealBanatvala N, Griffin PM, Greene KD, et al. The United States National Prospective Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome Study: microbiologic, serologic, clinical, and epidemiologic findings. J Infect Dis 2001;183:1063--70. CDC. Escherichia coli O111:H8 outbreak among teenage campers---Texas, 1999. MMWR 2000;49:321--4. Mahon BE, Griffin PM, Mead PS, Tauxe RV. Hemolytic uremic syndrome surveillance to monitor trends in infection with Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga toxin-producing E. coli [Letter]. Emerg Infect Dis 1997;3:409--12. Available in the Internet at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol3no3/mahon.htm>. Siegler RL, Pavia AT, Christofferson RD, Milligan MK. A 20year populationbased study of postdiarrheal hemolytic uremic syndrome in Utah. Pediatrics 1994;94:35--40. GonorrheaCDC. Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance 2000 supplement: Gonococcal Isolate Surveillance Project (GISP) annual report---2000. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, October 2001. Fox KK, del Rio C, Holmes KK, et al. Gonorrhea in the HIV era: a reversal in trends among men who have sex with men. Am J Public Health 2001;91:959--64. CDC. Gonorrhea---United States, 1998. MMWR 2000;49:538--42. Haemophilus influenzae, Invasive DiseaseGalil K, Singleton R, Levine OS, et al. Reemergence of invasive Haemophilus influenzae type b disease in a wellvaccinated population in remote Alaska. J Infect Dis 1999;179:101--6. Bisgard KM, Kao A, Leake J, Strebel PM, Perkins BA, Wharton M. Haemophilus influenzae invasive disease in the United States, 1994--1995: near disappearance of a vaccine-preventable childhood disease. Emerg Infect Dis 1998;2:229--37. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol4no2/bisgard.htm>. Hantavirus Pulmonary SyndromeGlass G, Cheek J, Patz J, et al. Using remotely sensed data to identify areas at risk for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis 2000;6:238--47. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol6no3/glass.htm>. Hjelle B, Glass G. Outbreak of hantavirus infection in the four corners region of the United States in the wake of the 1997--1998 El Nino-Southern Oscillation. J Infect Dis 2000;181:1569--73. Available at <http://www.journals.uchicago.edu/JID/journal/issues/v181n5/991334/brief /99134.abstract.html>. Chapman LE, Mertz GJ, Peters CJ, et al. Intravenous ribavirin for hantavirus pulmonary syndrome: safety and tolerance during 1 year of open-label experience. Antiviral Therapy 1999;4:211--9. Abstract available at <http://www.intmedpress.com/journals_avt_abst404_3.cfm>. Kitsutani PI, Denton RW, Fritz CL, et al. Acute Sin Nombre hantavirus infection without pulmonary syndrome, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 1999;5:701--5. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol5no5/kitsutani.htm>. Hepatitis ABell BP, Shapiro CN, Alter MJ, et al. The diverse patterns of hepatitis A epidemiology in the United States---implications for vaccination strategies. J Infect Dis 1998;178:1579--84. Lemon SM, Shapiro CN. The value of immunization against hepatitis A. Infect Agents Dis 1994;3:38--49. Shapiro CN, Coleman PJ, McQuillan GM, Alter MJ, Margolis HS. Epidemiology of hepatitis A: seroepidemiology and risk groups in the USA. Vaccine 1992;10(suppl 1):S59--S62. Hepatitis BMcQuillan GM, Coleman PJ, KruszonMoran D, Moyer LA, Lambert SB, Margolis HS. Prevalence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1976 through 1994. Am J Pub Health 1999;89:14--8. Coleman PJ, McQuillan GM, Moyer LA, Lambert SB, Margolis HS. Incidence of hepatitis B virus infection in the United States, 1976--1994: estimates from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys. J Infect Dis 1998;178:954--9. Margolis HS, Alter MJ, Hadler SC. Hepatitis B: evolving epidemiology and implications for control [Review]. Semin Liver Dis 1991;11:84--92. Hepatitis C; Non-A, Non-BArmstrong GA, Alter MJ, McQuillan GM, Margolis HS. The past incidence of hepatitis C virus infection: implications for the future burden of chronic liver disease in the United States. Hepatology 2000;31:777--82. Alter MJ, Kruszon-Moran D, Nainan OV, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med 1999;341:556--62. HIV Infection, Adult and PediatricCDC. HIV and AIDS---United States, 1981--2000. MMWR 2001;50:430--4. CDC. US HIV and AIDS cases reported through June 2000. Mid-year edition. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2000;12(No. 1):1--42. Lindegren ML, Steinberg S, Byers RH, Jr. Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS in children. Pediatr Clin N Am 2000;47:1--20. Lyme DiseaseCDC. Lyme disease---United States, 1999. MMWR 2001;50:181--5. Hayes EB, Maupin GO, Mount GA, Piesman J. Assessing the prevention effectiveness of local Lyme disease control. J Public Health Manag Pract 1999;5:84--92. MalariaLobel HO, Kozarsky PE. Update on prevention of malaria for travelers. JAMA 1997;278:1767--71. Zucker JR. Changing patterns of autochthonous malaria transmission in the United States: a review of recent outbreaks. Emerg Infect Dis 1996;2:37--43. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol2no1/zuckerei.htm>. Zucker JR, Campbell CC. Malaria: principles of prevention and treatment [Review]. Infect Dis Clin North Am 1993;7:547--67. MeaslesCDC. Measles---United States, 1999. MMWR 2000;49:557--60. CDC. Epidemiology of measles---United States, 1998. MMWR 1999;48:749--53. CDC. Measles---United States, 1997. MMWR 1998;47:273--6. Meningococcal DiseaseDiermayer M, Hedberg K, Hoesly FC, et al. Epidemic serogroup B meningococcal disease in Oregon: the evolving epidemiology of the ET5 strain. JAMA 1999;281:1493--7. Available at <http://jama.amaassn.org/issues/v281n16/rfull/joc81215.html>. Rosenstein NE, Perkins BA, Stephens DS, et al. The changing epidemiology of meningococcal disease in the United States, 1992--1996. J Infect Dis 1999;180:1894--901. MumpsCDC. Mumps surveillance United States, 1988--1993. MMWR 1995;44(No. SS3). Briss PA, Fehrs LJ, Parker RA, et al. Sustained transmission of mumps in a highly vaccinated population: assessment of primary vaccine failure and waning vaccine-induced immunity. J Infect Dis 1994;169:77--82. Hersh BS, Fine PE, Kent WK, et al. Mumps outbreak in a highly vaccinated population. J Pediatr 1991;119:187--93. PertussisBisgard KM, Christie CD, Reising SF, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Bordetalla pertussis by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis profile: Cincinnati, 1989--1996. J Inf Dis 2001;183:1360--7. Strebel P, Nordin J, Edwards K, et al. Population-based incidence of pertussis among adolescents and adults, Minnesota, 1995--1996. J Inf Dis 2001;183:1353--9. Guris D, Strebel PM, Bardenheier B, et al. Changing epidemiology of pertussis in the United States: increasing reported incidence among adolescents and adults, 1990--1996. Clin Infect Dis 1999;28:1230--7. PlagueInglesby TV, Dennis DT, Henderson DA, et al. Plague as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. Working Group on Civilian Biodefense [Review]. JAMA 2000;283:2281--90. Dennis DT, Gage KL, Gratz N, Poland JD, Tikhomirov E. Plague manual: epidemiology, distribution, surveillance and control. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 1999. Poland JD, Dennis DT. Plague. In: Evans AS, Brachman PS, eds. Bacterial infections of humans: epidemiology and control. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Plenum Medical Book Company, 1998:545--58. Poliomyelitis, ParalyticPrevots DR, Khetsuriani N, Wharton M. Evidence for a decline in the number of vaccine-associated paralytic poliomyelitis cases in the United States following implementation of a sequential poliovirus vaccination schedule, 1997--1998. Presented at the 36th annual meeting of the Infectious Disease Society of America, November 12--15, 1998. Prevots DR, Sutter RW, Strebel PM, Weibel RE, Cochi SL. Completeness of reporting for paralytic poliomyelitis, United States, 1980 through 1991. Implications for estimating the risk of vaccine-associated disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1994;148:479--85. Q FeverRaoult D, Tissot-Dupont H, Foucault C, et al. Q fever 1985--1998. Clinical and epidemiologic features of 1,383 infections. Medicine 2000:79:109--23. Tissot-Dupont H, Torres S, Nezri M, Raoult D. Hyperendemic focus of Q fever related to sheep and wind. Am J Epi 1999;150:67--74. CDC. Q fever outbreak---Germany, 1996. MMWR 1997;46:29--32. Bernard KW, Parham GL, Winkler WG, Helmick CG. Q fever control measures: recommendations for research facilities using sheep. Infection Control 1982;3:461--5. Rabies, Animal and HumanKrebs JW, Rupprecht CE, Childs JE. Rabies surveillance in the United States during 1999. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2000;217:1799--811. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvrd/rabies/professional/Surveillance99/index.htm>. Noah DL, Drenzek CL, Smith JS, et al. Epidemiology of human rabies in the United States, 1980 to 1996 [Review]. Ann Intern Med 1998;128:922--30. Rocky Mountain Spotted FeverTreadwell TA, Holman RC, Clarke MA, Krebs JW, Paddock CD, Childs JE. Rocky Mountain spotted fever in the United States, 1993--1996. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2000;63:21--6. Paddock CD, Greer PW, Ferebee TL, et al. Hidden mortality attributable to Rocky Mountain spotted fever: immunohistochemical detection of fatal, serologically unconfirmed diseases. J Infect Dis 1999;179:1469--76. Dalton MJ, Clarke MJ, Holman RC, et al. National surveillance for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, 1981--1992: epidemiologic summary and evaluation of risk factors for fatal outcome. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1995;52:405--13. Rubella and Rubella, Congenital SyndromeCDC. Rubella among Hispanic adults---Kansas, 1998, and Nebraska, 1999. MMWR 2000;49:225--8. Danovaro-Holliday MC, LeBaron CW, Allensworth C, et al. A large rubella outbreak with spread from the workplace to the community. JAMA 2000;284:2733--9. Reef S, Plotkin S, Cordero J, et al. Preparing for congenital rubella syndrome elimination: summary of the Workshop on Congenital Rubella Syndrome Elimination in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2000;31:85--95. SalmonellosisOlsen SJ, Bishop R, Brenner FW, et al. The changing epidemiology of Salmonella: trends in serotypes isolated from humans in the United States, 1987--1997. J Infect Dis 2001;183:753--61. Mahon BE, Slusker L, Hutwagner L, et al. Consequences in Georgia of a nationwide outbreak of Salmonella infections: what you don't know might hurt you. Am J Public Health 1999;89:31--5. Van Beneden CA, Keene WE, Strang RA, et al. Mutinational outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype Newport infections due to contaminated alfalfa sprouts. JAMA 1999;281:158--62. Glynn MK, Bopp C, Dewitt WK, Dabney P, Moktar M, Angulo FJ. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium DT104 infections in the United States. N Engl J Med 1998;338:1333--8. ShigellosisSobel J, Cameron DN, Ismail J, et al. A prolonged outbreak of Shigella sonnei infections in traditionally observant Jewish communities in North America caused by a molecularly distinct bacterial subtype. J Infect Dis 1998;177:1405--8. MohleBoetani JC, Stapleton M, Finger R, et al. Communitywide shigellosis: control of an outbreak and risk factors in child daycare centers. Am J Public Health 1995;85:812--6. Streptococcal Disease, Invasive, Group ACDC. Active Bacterial Core Surveillance (ABCs) report. Emerging Infections Program Network. Group A streptococcus, 2000 (preliminary). Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, 2000. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dbmd/abcs/survreports/gas00prelim.pdf>. Laupland KB, Davies HD, Low DE, Schwartz B, Green K, McGeer A. Invasive group A streptococcal disease in children and association with varicella-zoster virus infection. Ontario Group A Streptococcal Study Group. Pediatrics 2000;105:E60. Anonymous. Prevention of invasive group A streptococcal disease among household contacts of case-patients: is prophylaxis warranted? The Working Group on Prevention of Invasive Group A Streptococcal Infections. JAMA 1998;279:1206--10. Streptococcus pneumoniae, DrugResistant, Invasive DiseaseRobinson KA, Baughman W, Rothrock G, et al. Epidemiology of invasive Streptococcus pneumoniae infections in the United States, 1995--1998: opportunities for prevention in the conjugate vaccine era. JAMA 2001;285:1729--35. Whitney CG, Farley MM, Hadler J, et al. Increasing prevalence of multidrug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae in the United States. N Engl J Med 2000;343:1917--24. Syphilis, CongenitalCDC. Congenital syphilis---United States, 2000. MMWR 2001;50:573--7. Southwick KL, Guidry HM, Weldon MM, Mertz KJ, Berman SM, Levine WC. An epidemic of congenital syphilis in Jefferson County, Texas, 1994--1995: inadequate prenatal syphilis testing after an outbreak in adults. Am J Public Health 1999;89:557--60. CDC. Guidelines for the prevention and control of congenital syphilis. MMWR 1988;37(No. S1). Syphilis, Primary and SecondaryCDC. Primary and secondary syphilis---United States, 1999. MMWR 2001;50:113--7. CDC. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance supplement 2000: syphilis surveillance report. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, December 2001. CDC. The national plan to eliminate syphilis from the United States. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, October 1999. TetanusCDC. Neonatal tetanus---Montana, 1998. MMWR 1998;47:928--30. CDC. Tetanus among injecting drug users---California, 1997. MMWR 1998;47:149--51. Gergen PJ, McQuillan GM, Kiely M, EzzatiRice TM, Sutter RW, Virella G. A population-based serologic survey of immunity to tetanus in the United States. N Engl J Med 1995;332:761--6. ToxicShock SyndromeHajjeh RA, Reingold R, Weil A, Shutt K, Schuchat A, Perkins BA. Toxic shock syndrome in the United States: surveillance update, 1979--1996. Emerg Infec Dis 1999;5:807--10. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol5no6/hajjeh.htm>. Schuchat A, Broome CV. Toxic shock syndrome and tampons. Epidemiol Rev 1991;13:990112. Gaventa S, Reingold AL, Hightower AW, et al. Active surveillance for toxic shock syndrome in the United States, 1986. Rev Infect Dis 1989;11(suppl):S28--S34. TuberculosisCDC. Reported tuberculosis in the United States, 2000. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC, August 2001. Available at <http://www.cdc.gov/nchstp/tb/>. Institute of Medicine. Ending neglect: the elimination of tuberculosis in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2000. Available at <http://www.nap.edu/books/0309070287/html/>. Talbot EA, Moore M, McCray E, Binkin NJ. Tuberculosis among foreign-born persons in the United States, 1993--1998. JAMA 2000;284:2894--900. TrichinosisMoorhead A, Grunenwald PE, Dietz VJ, Schantz PM. Trichinellosis in the United States, 1991--1996: declining but not gone. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999;60:66--9. McAuley JB, Michelson MK, Schantz PM. Trichinosis surveillance, United States, 1987--1990. In: CDC surveillance summaries, December 1991. MMWR 1991;40(No. SS3):35--42. TularemiaDennis DT, Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, et al. Tularemia as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA 2001;285:2763--73. Typhoid FeverAckers ML, Puhr ND, Tauxe RV, Mintz ED. Laboratory-based surveillance of Salmonella Serotype Typhi infections in the United States: antimicrobial resistance on the rise. JAMA 2000;283:2668--73. Mermin JH, Villar R, Carpenter J, et al. A massive epidemic of multidrugr-esistant typhoid fever in Tajikistan associated with consumption of municipal water. J Infect Dis 1999;179:1416--22. Mermin JH, Townes JM, Gerber M, Dolan N, Mintz ED, Tauxe RV. Typhoid fever in the United States, 1985--1994: changing risks of international travel and increasing antimicrobial resistance. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:633--8. Varicella, Varicella DeathsCDC. Varicella-related deaths---Florida, 1998. MMWR 1999;48:379--81.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 6/3/2002 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 6/3/2002

|