|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

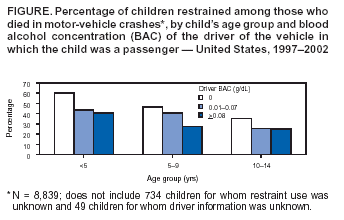

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Child Passenger Deaths Involving Drinking Drivers --- United States, 1997--2002Please note: An erratum has been published for this article. To view the erratum, please click here. Motor-vehicle crashes are the leading cause of death among children aged >1 year in the United States (1), and one in four crash-related deaths among child passengers aged <14 years involves alcohol use (2). To characterize the occurrence of child passenger deaths involving drinking drivers during 1997--2002, CDC analyzed data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. This report summarizes the results of that analysis, which indicated that among the 2,355 children who died in alcohol-related crashes, 1,588 (68%) were riding with drinking drivers; the majority of these children were not restrained. To reduce the number of child fatalities in alcohol-related motor-vehicle crashes, effective interventions are needed to prevent alcohol-impaired driving and to increase use of child passenger restraints. FARS is a census of fatal motor-vehicle crashes that occur on public roadways in the United States and result in the death of an occupant or nonoccupant (e.g., pedestrian or bicyclist) within 30 days of the crash. A fatal motor-vehicle crash was classified as alcohol related if either a driver or nonoccupant had a blood alcohol concentration (BAC) of >0.01 g/dL. When BACs were not available, they were imputed from driver and crash characteristics by using a two-stage estimation procedure (3). A drinking driver was defined as a driver with a measured or imputed BAC of >0.01 g/dL. Child passengers were defined as passengers aged <14 years. During 1997--2002, a total of 9,622 child passengers died in motor-vehicle crashes; 2,335 (24%) were killed in crashes involving drinking drivers. Of the 2,061 alcohol-related crashes involving drinking drivers in which children were killed, 1,624 (79%) involved at least one driver with a BAC of >0.08 g/dL (in 31 states as of December 31, 2002, the legal BAC level for drivers aged >21 years is <0.08 g/dL). Of these crashes, 1,238 (60%) occurred during 6 a.m.--9 p.m. Of the 2,335 children who died in alcohol-related crashes, 1,588 (68%) were riding with drinking drivers (Table). The median BAC of the 1,409 drinking drivers who were transporting children was 0.13 g/dL (range: 0.01--0.65 g/dL). Of the 1,409 drinking drivers involved in these crashes, 956 (68%) survived. For all child passenger deaths, including those not involving drinking drivers, child passenger restraint use decreased as both the child's age and BAC of the child's driver increased (Figure). Of 1,451 child passengers with known restraint information who died while riding with drinking drivers, 466 (32%) were restrained at the time of the crash. Reported by: RA Shults, PhD, Div of Unintentional Injury Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, CDC. Editorial Note:The findings in this report indicate that during 1997--2002, approximately 390 children died annually in alcohol-related crashes in the United States. The majority of children who died while riding with drinking drivers were not restrained at the time of the crash. The majority of drivers in these crashes survived, suggesting that certain children killed in alcohol-related crashes might have survived had they been restrained properly. Strong enforcement of child safety-seat laws and passage of primary enforcement safety-belt laws (i.e., laws that allow police to stop and ticket a driver solely because an occupant is unbelted) in all states could further reduce child passenger deaths. Because 60% of alcohol-related crashes involving child passenger deaths occurred during 6 a.m.--9 p.m., enforcement activities of child safety-seat and safety-belt laws (e.g., roadside checkpoints) are needed, especially during daylight hours. Drinking drivers have higher rates of severe crashes (4); for this reason, stricter enforcement of restraint laws might substantially reduce the number of deaths of children who are transported by these drivers. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, because BAC data are imputed for approximately 60% of FARS cases (3), the precision of the reported BACs is reduced. Second, for crashes in which a child's driver survived, driver alcohol use might have been underreported because alcohol testing is more complete among fatalities (5). Finally, information about restraint use is obtained from police crash reports, which might overreport restraint use (6). To decrease alcohol-related crash fatalities among child passengers, communities should implement effective strategies to reduce alcohol-impaired driving, particularly among drivers who transport children. Effective policies that apply to the general driving population include sobriety checkpoints (7), lower legal BACs (e.g., <0.08 g/dL) (7), administrative license suspension (8), and mandatory substance-abuse assessment and treatment for persons convicted of driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol (9). Strategies to deter persons from drinking and driving with children might include lower legal BAC limits for drivers transporting children and child endangerment laws that apply to persons who drive while intoxicated with a child in the vehicle (2). Such laws have been enacted in 35 states (10); however, the effectiveness of these laws has not been evaluated. Families and caregivers can reduce the risk to child passengers by adopting a "zero tolerance" policy regarding alcohol consumption when transporting children. When health-care providers advise caregivers about injury risks to children, they should counsel against drinking and driving. Health-care providers treating adults can screen patients for alcohol-related problems and provide them with brief interventions or refer them to treatment, as needed. Additional information regarding effective community-based interventions to increase child safety-seat and safety-belt use and to reduce alcohol-impaired driving is available from the Task Force on Community Preventive Services at http://www.thecommunityguide.org. Information about alcohol-impaired driving and child passenger safety is available from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration at http://www.nhtsa.dot.gov. Information about child endangerment laws is available from Mothers Against Drunk Driving at http://www.madd.org. Acknowledgments This report is based on contributions from T Lindsey, National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, Washington, DC. KP Quinlan, MD, Dept of Pediatrics, Univ of Chicago, Illinois. References

Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 2/5/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 2/5/2004

|