|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

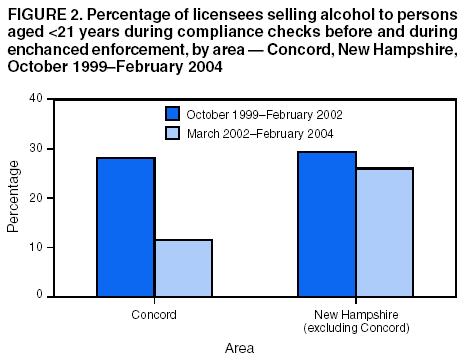

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Enhanced Enforcement of Laws to Prevent Alcohol Sales to Underage Persons --- New Hampshire, 1999--2004In 1984, the National Minimum Drinking Age Act (Public Law 98-363) was passed, requiring states to raise to 21 years the minimum age to purchase and publicly possess alcohol. Although the law has contributed to substantial reductions in underage drinking and alcohol-related motor-vehicle crashes (1), alcohol use and binge drinking rates among youths remain high in the United States, and efforts by youths to purchase alcohol from licensed establishments frequently are successful (2,3). To reduce alcohol sales to persons aged <21 years in Concord (2000 population: 40,687), New Hampshire, the Concord Police Department (CPD) and New Hampshire Liquor Commission (NHLC) conducted a pilot program of enhanced law enforcement with quarterly compliance checks of alcohol licensees during March 2002--February 2004. This report summarizes the results of that program, which indicated that enhanced enforcement 1) resulted in a 64% reduction in retail alcohol sales to underage youths and 2) was temporally associated with declines in alcohol use and binge drinking among Concord high school students. These findings emphasize the potential effectiveness of enhanced enforcement of minimum drinking age laws to reduce consumption of alcohol by underage youths. NHLC routinely conducts statewide compliance checks by using persons aged 17--19 years to attempt purchases of beer or wine. If questioned, buyers are instructed to state their true age and, if asked, to present their driver's license to verify their age. During October 1999--February 2004, routine compliance checks were conducted at 29% (539 of 1,839) of "off-sale" alcohol licensees (i.e., businesses that sell alcohol to be consumed off-premises, such as convenience, grocery, and state liquor stores) outside of Concord each year. In Concord, during October 1999--February 2002, routine compliance checks were conducted one to two times per year at all off-sale alcohol licensees. During March 2002--February 2004, CPD conducted a campaign of increased enforcement of the minimum drinking age. The campaign included three components: 1) quarterly compliance checks of all off-sale alcohol licensees; 2) enhanced administrative penalties for noncompliance, including a mandatory fine levied against the alcohol licensee, temporary suspension of retailers' alcohol licenses beginning with the first offense, and increasing penalties for subsequent offenses (Table); and 3) media coverage of enhanced enforcement activities, such as reporting the number of citations issued for noncompliance. Quarterly compliance checks were conducted throughout the intervention period; however, mandatory licensee fines and suspensions were in effect only during August 2002--July 2003. The enhanced administrative penalties were announced by CPD in a letter sent to all Concord alcohol licensees in June 2002. Under New Hampshire state law, store clerks who sold alcoholic beverages to underage buyers also were subject to fines and penalties, which were issued at the discretion of the local judicial system throughout the study period. To estimate the number of youths who drank alcohol, the New Hampshire Department of Health and Human Services analyzed data from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) conducted at Concord High School among students in grades 9--12 in 2001 and 2003. In 2001, a total of 1,131 (62.0%) of 1,824 high school students participated in the Concord YRBS. In 2003, a total of 1,274 (74.0%) of 1,721 students participated. Statewide data on alcohol consumption by high school students were obtained from the 1995 and 2003 YRBS conducted by New Hampshire. Because of low response rates in 1997, 1999, and 2001, data from New Hampshire YRBS surveys in those years were not weighted, and therefore were not used for comparison. In 1995, a total of 2,092 students participated in the New Hampshire YRBS; the overall response rate was 65.0%. In 2003, a total of 1,322 students participated in the New Hampshire YRBS; the overall response rate was 61.8%. Current alcohol use was defined as having at least one drink of alcohol on >1 day during the preceding 30 days. Binge drinking was defined as having five or more drinks of alcohol in a row during the preceding 30 days. In Concord, before enhanced enforcement activities, 62 (28.2%) of 220 licensees sold alcohol to underage youths during compliance checks (Figure 1). During enhanced enforcement, 39 (10.2%) of 383 licensees sold alcohol to underage youths during compliance checks (relative risk [RR] = 0.4; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.3--0.5). During enforcement checks elsewhere in New Hampshire, outside of Concord, 308 (30.5%) of 1,007 licensees sold alcohol to underage youths in compliance checks during October 1999--February 2002 (Figure 2). During March 2002--February 2004, a total of 231 (27.7%) of 832 licensees sold alcohol to underage youths (RR = 0.9; 95% CI = 0.8--1.1). Among Concord high school students, statistically significant declines occurred in the proportion of students who reported current alcohol use (from 49.8% in 2001 to 39.9% in 2003; RR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.7--0.9) and binge drinking (from 32.0% in 2001 to 25.0% in 2003; RR = 0.8; 95% CI = 0.7--0.9). Statewide, no statistically significant decreases occurred in the proportion of New Hampshire high school students who reported current alcohol use in 1995 (53.1% [95% CI = 50.2%--56.0%]) versus 2003 (47.1% [95% CI = 41.8%--52.4%]) or binge drinking in 1995 (32.9% [95% CI = 30.2%--35.6%]) versus 2003 (30.6% [95% CI = 25.9%--35.3%]). Reported by: R Barry, Concord Police Dept; E Edwards, New Hampshire Liquor Commission; A Pelletier, MD, New Hampshire Dept of Health and Human Svcs. R Brewer, MD, J Miller, MD, T Naimi, MD, Div of Adult and Community Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; A Redmond, MPH, Div of Applied Public Health Training, Epidemiology Program Office; L Ramsey, PhD, EIS Officer,CDC. Editorial Note:In Concord, New Hampshire, quarterly compliance checks and mandatory penalties were associated with substantial reductions in retail alcohol sales to underage buyers. During this same period, retail alcohol sales to underage buyers in the rest of the state remained unchanged. In addition, both current alcohol use and binge drinking by Concord high school students decreased during 2001--2003. These findings are consistent with other studies that determined compliance checks can reduce alcohol sales to underage youths and, when combined with other activities, might reduce youth consumption of alcohol (2,4,5). This report is subject to at least four limitations. First, during the study period, other efforts to reduce underage access to alcohol in Concord were conducted (e.g., roving park patrols and surveillance outside retail stores), reducing the likelihood that reduction in alcohol sales to underage youths was associated only with enhanced enforcement. Second, because quarterly compliance checks were instituted for a longer period than mandatory penalties, the contributions of the checks and penalties relative to the decrease in alcohol sales to underage youths were difficult to assess. Third, because statewide compliance checks were conducted by using a convenience sample, statistical comparisons could not be made between compliance check data for Concord and the rest of New Hampshire. Finally, the absence of weighted data from the 2001 New Hampshire YRBS limited the ability to compare recent changes in current alcohol use and binge drinking between Concord and the rest of the state. State and local governments often lack adequate resources to enforce minimum drinking age laws (6). CPD was able to partially fund its program through a grant from the New Hampshire Department of Justice. Alcohol excise taxes might be another resource for funding enforcement efforts. In addition, raising alcohol taxes is an effective policy intervention for reducing underage drinking and alcohol-related problems (6,7). The findings in this report support recommendations of the Institute of Medicine in its 2003 report, Reducing Underage Drinking: A Collective Responsibility (2). These recommendations call for 1) regular compliance checks; 2) administrative penalties, including fines and license suspensions that increase with each offense; 3) enhanced media coverage of the purposes and results of compliance checks; and 4) training for alcohol retailers regarding their legal responsibility to avoid selling alcohol to underage youths. These recommendations have been supported by previous studies (4,8,9). In another effort to prevent underage drinking, the New Hampshire state legislature in August 2003 approved a new driver's license that will display photo and driver information vertically for persons aged <21 years and horizontally for persons aged >21 years, making it easier for store clerks to identify underage youths. Acknowledgements This report is based in part on contributions by E Crane, J Madden, D Reilly, Concord Police Dept; A Moore, JD, New Hampshire Liquor Commission. J Magri, MD, Div of Applied Public Health Training, Epidemiology Program Office, CDC. References

Figure 1  Return to top. Figure 2  Return to top. Table  Return to top.

Disclaimer All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from ASCII text into HTML. This conversion may have resulted in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users should not rely on this HTML document, but are referred to the electronic PDF version and/or the original MMWR paper copy for the official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Page converted: 6/3/2004 |

|||||||||

This page last reviewed 6/3/2004

|