|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| ||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

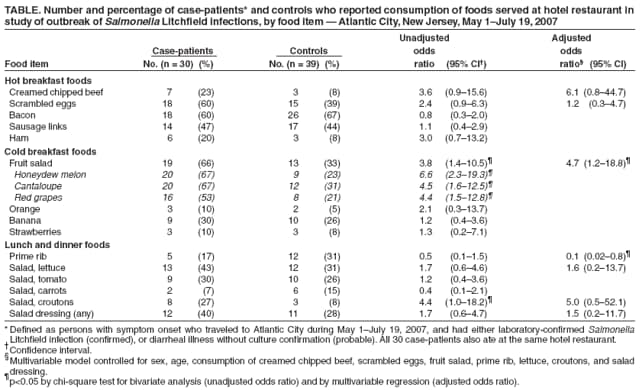

Persons using assistive technology might not be able to fully access information in this file. For assistance, please send e-mail to: [email protected]. Type 508 Accommodation and the title of the report in the subject line of e-mail. Salmonella Litchfield Outbreak Associated with a Hotel Restaurant --- Atlantic City, New Jersey, 2007On July 10, 2007, the Pennsylvania Department of Health notified the New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services (NJDHSS) of three culture-confirmed cases of Salmonella Litchfield infection with matching pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) patterns. Data from PulseNet, the national molecular subtyping network for foodborne disease surveillance, confirmed 11 cases (including the three from Pennsylvania) of this rarely identified Salmonella serotype in five states during a 5-week period; seven of the 11 patients had reported recent travel history to Atlantic City, New Jersey. This report describes the subsequent investigation led by NJDHSS and the Atlantic City Health Department (ACHD), which associated the outbreak with a hotel restaurant in Atlantic City. In all, 30 confirmed or probable cases of illness with S. Litchfield infection were identified among persons from eight states who had eaten at the hotel restaurant, including 10 restaurant food handlers. Investigators concluded that the outbreak most likely was associated with fruit salad, particularly the honeydew melon component, and that contamination likely resulted from an ill food handler. This investigation illustrates the potential for recurring food contamination by ill and asymptomatic food handlers and underscores the utility of PulseNet to link illnesses that might appear unrelated. Epidemiologic and Environmental InvestigationRoutine food histories collected from the initial three persons in Pennsylvania with confirmed S. Litchfield infection indicated a common exposure to the breakfast buffet at the same hotel restaurant in Atlantic City. During May 1--July 19, investigators later learned, the restaurant served approximately 7,300 breakfasts, 1,300 lunches, and 2,700 dinners. Forty-five persons worked in the restaurant, including some who spoke and understood only languages other than English. Signs in the restaurant were in English only. On July 12, the investigative team, including representatives from NJDHSS, ACHD, the Atlantic County Division of Public Health, and CDC visited the restaurant during the breakfast service to advise hotel management of the outbreak, collect food samples, interview food handlers, request stool specimens, and assess sanitation practices. Based on initial findings, ACHD directed the complete disinfection of the restaurant's main kitchen on July 13. Three recent ACHD inspections had revealed improper bare hand contact with food items, inadequate food temperature control, and other food-handling and storage violations, yielding a rating of "conditionally satisfactory." A total of 36 food and beverage items served during the preceding 24 hours were collected. Food samples collected during the inspection included a fruit salad consisting of red grapes, honeydew melon, and cantaloupe. The fruit salad was prepared from whole fruit purchased from a local wholesaler, cut onsite either the night before or the morning of service by any of six cooks, and refrigerated. The fruit salad later was handled by any of 20 servers and placed over an ice bath for 4 hours during the breakfast buffet. The New Jersey Public Health and Environmental Laboratories tested 12 items thought most likely to harbor Salmonella bacteria: red grapes, honeydew melon, cantaloupe, strawberries, parsley, ice, dispensed water, orange juice, iced tea, grapefruit juice, cranberry juice, and apple juice. However, no Salmonella species were cultured from any of these foods or beverages. On July 19, Salmonella group C was isolated from seven of 12 food handler stool specimens collected during July 12--July 13. ACHD ordered the restaurant to close immediately. Investigators collected samples from the food remaining in the kitchen, which was then disinfected thoroughly a second time; all leftover food was destroyed. The following week, two additional food handlers tested positive for S. Litchfield, and another reported symptoms that met the probable case definition, bringing to 10 the total number of food handlers with illness meeting the case definition. The restaurant reopened on August 1 with limited operation, staffed only by food handlers with confirmed negative stool test results. The hotel and restaurant property had been sold before the outbreak, and operations ceased permanently in September 2007. To determine the extent of the outbreak, on July 10, NJDHSS called for reports of additional cases via PulseNet and the CDC Epidemic Information Exchange (Epi-X). Cases were defined as illness in persons who traveled to Atlantic City during May 1--July 19, 2007 and who had either laboratory-confirmed S. Litchfield infection (for confirmed cases) or diarrheal illness without culture confirmation (for probable cases). Nationwide, a total of 20 probable or confirmed cases were reported in patrons who had dined at the Atlantic City restaurant under investigation. Investigators also interviewed 41 (91%) of the 45 food handlers who had worked at the restaurant since July 1. Five others who had stopped working at the restaurant before July 1 could not be contacted. The 30 persons who met the case definition (20 restaurant patrons and 10 food handlers) included four (13%) with probable cases and 26 (87%) with confirmed cases (17 patrons and nine food handlers). Isolates from all 26 culture-confirmed cases had matching PFGE patterns (XbaI pattern JGXX01.0004). Illness onset dates among the 30 persons who met the case definition ranged from May 31 to July 19 (Figure). Median age was 51 years (range: 13--84 years); 50% were female. The 30 persons were from New Jersey (12), Pennsylvania (nine), New York (three), Maryland (two), and Colorado, Connecticut, Michigan, and Ohio (one each). Twenty-three (77%) of the 30 persons reported diarrhea (defined as three or more loose stools during 24 hours), 21 (70%) reported abdominal cramps, 16 (53%) fever, eight (27%) vomiting, and five (17%) bloody diarrhea. Eighteen (60%) of the 30 sought medical care, and six were hospitalized. No deaths occurred. All 20 of the patrons who met the case definition reported at least one symptom consistent with salmonellosis; of the 10 ill restaurant workers, four (three with confirmed cases and one probable) reported symptoms, and none sought medical care. Case-Control StudyTo determine common food exposures, investigators conducted a case-control study of restaurant patrons and workers. Controls were defined as well dining companions of patrons who consumed at least one restaurant meal or well restaurant workers who ate at least three restaurant meals during May 1--July 19. A detailed interview was conducted to collect exposure data for all food items available in the restaurant. Case-control data were analyzed using bivariate and multivariable logistic regression; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated, and associations were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. A total of 30 case-patients and 39 controls were enrolled in the study. No statistically significant differences in age and sex distribution were observed between case-patients and controls. Bivariate analysis indicated increased likelihood of illness among consumers of salad croutons (unadjusted odds ratio [OR] = 4.4), fruit salad (OR = 3.8), and each of the three fruits in the salad: honeydew melon (OR = 6.6), cantaloupe (OR = 4.5), and red grapes (OR = 4.4) (Table). Multivariable analysis indicated that eating fruit salad was independently associated with S. Litchfield infection after controlling for age, sex, and consumption of other foods (adjusted OR = 4.7) (Table). Because of multicollinearity, the three components of the fruit salad could not be analyzed as separate variables in the multivariable model. However, when modeling the effect of only one fruit at a time in three separate models, eating honeydew melon had a stronger association with illness (OR = 10.0; CI = 2.1--47.7) than eating cantaloupe (OR = 5.4; CI = 1.3--22.7) or grapes (OR = 6.1; CI 1.5--24.5). Reported by: RL Cash, MPP, B Lyons, MSN, J Reinhard, P Simonetti, Atlantic City Health Dept.; EM Adler, MPH, Atlantic County Div of Public Health; E Bresnitz, MD, S Lee, M Malavet, MSA, SW Matiuck, C Robertson, MD, New Jersey Dept of Health and Senior Svcs. A Cronquist MPH, Colorado Dept of Public Health and Environment. P Mshar, Connecticut Dept of Public Heath. CS Kim, MPH, Maryland Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene. SA Bidol, MPH, Michigan Dept of Community Health. L Chicaiza, LS Kidoguchi, MPH, L Kornstein, PhD, New York City Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene; E Villamil, MPH, New York State Dept of Health. S Nowicki, MPH, Ohio Dept of Health. C Sandt, PhD, C Marriott, MPH, K Waller, MD, Pennsylvania Dept of Health. M Glenshaw, PhD, P Juliao, PhD, EIS officers, CDC. Editorial Note:This outbreak resulted in confirmed or probable cases of salmonellosis in at least 20 patrons and 10 food handlers, all of whom consumed food items from the same hotel restaurant in Atlantic City during a period of several weeks. Many other cases likely went unidentified because adults with salmonellosis often do not seek medical treatment that would enable their infections to be detected by PulseNet (1). A case-control study identified consumption of fruit salad, and particularly honeydew melon, as the food items most likely associated with illness. The cause of the outbreak likely was an ill restaurant worker who handled the fruit salad, and possibly other foods. This food handler was not identified and might have been one of five employees who stopped working at the restaurant before the outbreak investigation and could not be contacted. Recurring food contamination through the outbreak period by infected workers is plausible as a source of infection because 60% of workers with culture-confirmed illness were asymptomatic, and all 10 ill workers worked throughout probable infectious periods. Illness likely was underreported by workers; one culture-confirmed worker initially reported having no symptoms but later admitted to experiencing multiple loose stools in a 24-hour period. Foods other than fruit salad also might have been contaminated with Salmonella bacteria, but were not associated with illness in the multivariable analysis. The fruit salad was the only uncooked item prepared onsite and stored for several hours on the buffet and was the only food item with a statistically significant association with illness in the multivariable analysis. Since 1990, S. Litchfield has only been identified in four other foodborne outbreaks reported to CDC's Electronic Foodborne Outbreak Reporting System (eFORS) and represented only 0.4% of the 391,293 cases of Salmonella infection reported to the National Salmonella Surveillance System during 1995--2005 (3). Because of low salmonellosis reporting rates, this outbreak continued for approximately 6 weeks before cases were linked epidemiologically. The rare S. Litchfield serotype in this outbreak triggered the investigation that determined a common exposure source. Among S. Litchfield PFGE patterns reported to PulseNet, the one associated with this outbreak (XbaI pattern JGXX01.0004) is the one identified most frequently (16%). Melon can be a frequent reservoir of bacteria in salmonellosis outbreaks (2). During 1995--2006, eFORS reported that honeydew melon was associated with 15 (42%) of 36 melon-associated outbreaks. Although bacterial contamination in melons can occur before consumer purchase (4,5), no illnesses outside of workers and patrons of the implicated restaurant were reported in this outbreak. Fresh-cut melons left at room temperature for 5 hours harbor significantly higher counts of Salmonella bacteria compared with refrigerated melons (6). In the outbreak described in this report, the honeydew melon and other fruits in the fruit salad were placed routinely over an ice bath for 4 hours during the breakfast buffet, and patrons and workers might have consumed fruit served at inadequate temperatures once the ice melted. The findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations. First, results of the case-control study might have been limited by reporting bias and low statistical power. Second, workers with negative stool cultures might have underreported symptoms and, therefore, might have been misclassified. Finally, limited recall of patrons interviewed several weeks after visiting the restaurant might have resulted in underreporting or inaccurate reporting of exposure to food items. Restaurant and hotel managers should reinforce safe food-handling practices, including worker avoidance of all food-handling responsibilities during illness, particularly diarrhea. In addition, because restaurant workers might be fluent only in languages other English, appropriate instruction and signage should be provided in a language each worker can understand. Acknowledgments This report is based, in part, on contributions from K Adams, MPH, Atlantic County Div of Public Health; J Fagliano, PhD, ML Falco, MPH, W Manly, MA, New Jersey Dept of Health and Senior Svcs; TS Troppy, MPH, Massachusetts Dept of Health; V Reddy, MPH, New York City Dept of Health and Mental Hygiene; P Smith, MD, New York State Dept of Health; Y Khachadourian, T Quinlan, New York State Wadsworth Center Bacteriology Laboratory; V Dato, MD, L Lind, NK Rea, PhD, Pennsylvania Dept of Health; BW Kissler, MPH, US Dept of Agriculture; and K Bisgard, DVM, CDC. References

Table  Return to top. Figure  Return to top.

All MMWR HTML versions of articles are electronic conversions from typeset documents. This conversion might result in character translation or format errors in the HTML version. Users are referred to the electronic PDF version (http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr) and/or the original MMWR paper copy for printable versions of official text, figures, and tables. An original paper copy of this issue can be obtained from the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office (GPO), Washington, DC 20402-9371; telephone: (202) 512-1800. Contact GPO for current prices. **Questions or messages regarding errors in formatting should be addressed to [email protected].Date last reviewed: 7/17/2008 |

|||||||||

|